By Gene Ching

Tongzigong is one of the most spectacular forms of Shaolin kung fu, and yet it has no direct fighting applications. It is a fundamental building block of Shaolin practice, and yet it is too extreme for most practitioners to even begin to attempt. Its name implies youth, and yet its most celebrated practitioners are the elderly. It is one of Shaolin's deepest meditation techniques, and yet it is the centerpiece act in almost every Shaolin theatrical show that toured the globe over the last two decades. If ever there was a Shaolin koan, tongzigong is that tangled knot.

Tongzigong is one of the most spectacular forms of Shaolin kung fu, and yet it has no direct fighting applications. It is a fundamental building block of Shaolin practice, and yet it is too extreme for most practitioners to even begin to attempt. Its name implies youth, and yet its most celebrated practitioners are the elderly. It is one of Shaolin's deepest meditation techniques, and yet it is the centerpiece act in almost every Shaolin theatrical show that toured the globe over the last two decades. If ever there was a Shaolin koan, tongzigong is that tangled knot.

Tongzigong (童子功) is a discipline for the young. To achieve its highest levels, tongzigong must be practiced rigorously before the body is fully matured. Once the bones are set, mastery of this discipline is unattainable. The body must be molded as it grows. Tongzi means child, boy or virgin. Gong means work. It's actually the same character as kung in kung fu (功夫), which literally means skill, art, labor or effort. When taken literally, kung fu can embrace any manner of disciplines, from painting to craftsmanship. Only Westerners use the term exclusively to signify Chinese martial arts. In proper pinyin, the term is gongfu.

To the untrained eye, tongzigong is a spectacle of contortionism, a real show-stopper on stage. Contortionists have been an integral act in street performances and circus for centuries. Who isn)t impressed by a contortionist hooking their feet behind their shoulders? But for Shaolin practitioners, tongzigong is far more than just a circus act. Within tongzigong lies an internal cultivation that is key to the very essence of all Shaolin kung fu.

Kung Fu versus Yoga

It is very enticing to try to connect tongzigong to yoga because, to the untrained eye, both seem like steroidal stretching. This has become a popular assumption. A cursory review of the history of Shaolin and yoga debunks such claims. It all stems from Shaolin's touted link to India. Shaolin's most prominent creation legend tells of how Bodhidharma, an Indian monk, brought Buddhist teachings into China and founded Zen (or Chan in Mandarin 禪) and Shaolin kung fu. The introductory chapters of many kung fu books expound Bodhidharma's creation of yijinjing (易筋經), the Muscle Tendon Change Classic. This is recognized as the foundation for all Shaolin kung fu. Like tongzigong, yijinjing is a regimen for cultivating qi, so neither is directly applicable to combat. Consequently, tongzigong is often attributed to Bodhidharma as well. Many assume that because Bodhidharma was Indian, yijinjing and tongzigong must have been rooted in yoga. This is a faulty assumption on an apocryphal tale.

Yoga, like kung fu, has been generally misrepresented in the West. Just as kung fu is commonly restricted to self defense, yoga is misunderstood as a calisthenic health practice. The word yoga means union. It refers to a wide range of spiritual and mystical practices. The contortion-like poses which typify western misperceptions are only a fraction of yogic disciplines. Those poses are called asana, which literally means seat or posture. The asana stem from a branch called hatha yoga. Hatha yoga means forceful yoga, but there are dozens of other yogic practices which never adopt the stereotypical asana poses. Authentic yoga, and some might argue authentic kung fu, has a common purpose of spiritual awakening.

The invention of hatha yoga is often attributed to divine adept named Goraksha who lived in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. Goraksha is attributed as the author of the oldest hatha yoga scriptures, Siddha-Siddhanta-Paddhati (Track of the Doctrine of Adepts). It was after 1000 CE that hatha yoga began to thrive. This creates a glaring problem with the Bodhidharma yoga theory since Bodhidharma lived in the 5th century. It could be argued that hatha yoga derives from tantra and other older traditions, but given the dubiousness of Bodhidharma's connection to yijinjing, the argument that qigong emerged from yoga is delegated to those who forget history.

Shaolin versus Wudang

Like yijinjing, the origins of tongzigong are murky. If the popular Bodhidharma myth is ruled out, where might these disciplines have originated? In fact, most qigong forms trace their roots back to Daoism. Daoist qigong dates back thousands of years, predating any Shaolin claim by centuries. Like Daoism, qigong is a uniquely Chinese invention. Qigong contains parallel concepts to many other ancient forms of mysticism and self cultivation around the world, yoga being the most common comparison. However, qigong is truly unique with its conception of qi. Qigong practice is intimately tied to traditional Chinese medicine and the martial arts.

Wudang kung fu, the Daoist school often credited as the progenitor of tai chi, also has tongzigong within its curriculum. Since Wudang is considered an internal school and Shaolin external, Wudang has been cast as the eternal rival of Shaolin. Perhaps this longstanding contention has led some to attribute Wudang as the original source of tongzigong. Intriguingly enough, Wudang also has a yijinjing and a baduanjin (8 section brocade). Which faction was the actual originator of each of these qigong methods is still subject to debate.

In recent decades, China has seen an increase in qigong practice. In a strange twist of fate, qigong benefited from the spiritual vacuum created by the banning of religion during the Cultural Revolution. Although qigong is ingrained within Daoism and popular in Chinese Buddhism (and yes, there are even Christian and Muslim forms of qigong now), it is not intrinsically religious and so escaped some of the persecution from the Communists. In fact, it soon became endorsed as science by the Chicoms as a source of national pride and a method for public health care reform. In the )90s, qigong became very popular within China, so much so that there were backlashes against qigong cults. Most notable are the complex problems China has had with the Buddhist- and Daoist-derived qigong organization known as Falun Gong. Today, qigong has gained worldwide notoriety and enjoyed tremendous growth as a low impact exercise and a complementary therapy. Many hospitals in America now offer qigong classes as a preventative as well as a rehabilitative. However, you won't find tongzigong offered in any of those arenas. Shaolin tongzigong is an extreme form qigong. It's too challenging for most adults and too demanding for most children. Skilled tongzigong practitioners are rare and most are from Shaolin.

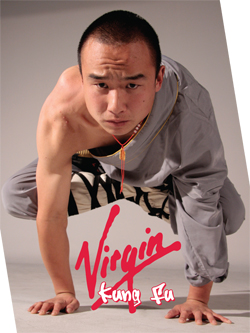

A Virgin Monk

At 23, Jin Le must train for at least an hour and a half every day to maintain his Shaolin tongzigong skills. A native of Henan Province, where Shaolin is located, Jin was enrolled at one of Shaolin's foremost academies, Henan Daxue Shaolin Wushu Xueyuen (河南大學少林武術學院), at age eleven. This school was under the direction of one of the "Eighteen Diamonds of Shaolin," Grandmaster Feng Genhuai (馮根怀). It once stood right across the street from the Temple's flagship school, the Shaolin Wushuguan. In the )90s, the Wushuguan was the designated school for foreigners and housed the official Shaolin warrior monk demonstration team. Jin was sent to Grandmaster Feng's school because one of his uncles, Jin Baoshen, was a head coach there.

Jin Le's family was not rich, so it was a privilege for him to be there. That was a major motivating factor because he never thought himself as capable as his kung fu brothers. He felt he couldn't quite grasp the teachings as naturally as the others. But rather than lose face for his family, he trained extra hard. While the other students took their naps, he continued to train himself. After dinner, he trained even more. He only remembers one thing from those days, and that one thing he sums up in one word: ku (bitter 苦).

Kung fu rewards those who can eat bitter. At age thirteen, Jin began studying tongzigong intensively. With his determination, he made good progress and eventually transferred to the Shaolin Wushuguan to study under his cousin, the warrior monk Shi Yanwei (Jin Pengwei). In 2001, he made the Shaolin Wuseng Biaoyandui (Warrior Monk Performance Team 少林武僧表演隊) and took the Shaolin name Shi Yanle. He toured all over China with the troupe, showcasing his skills in staff, double tiger hooks, taizu changquan, baduanjin and of course, tongzigong. He also performed in Singapore and Malaysia. In 2004, he first came to America in the entourage of Venerable Abbot Shi Yongxin.

Virgin's Work

According to Jin Le, the practice of tongzigong requires an intensive study of basics (jibengong基本功) and stretching. What's more, you have to include Chan meditation. Before practice, Jin meditates for thirty minutes to an hour. When he was learning tongzigong, he spent a lot of time meditating on the Buddhist statues and paintings at Shaolin Temple. He focused on the serenity of the expressions of the Buddha, the Bodhisattvas and Lohan. Sometimes, he even imitated the postures of the Lohan. Jin says that all of the spirit is in the eyes, and this is a key factor to good practice. He studied the Buddhist sutras too. All of this was necessary to get the right energy and proper mindset to practice tongzigong. Jin also confesses to researching as much as he could find about Indian yoga as well. Yoga resources were limited at Shaolin, but very helpful in his extracurricular studies of the art.

Like tai chi -- and hatha yoga too, for that matter -- tongzigong emphasizes a powerful combination of hardness and softness. As often quoted in tai chi, the practitioner must be soft like cotton, while hard like iron. In Jin's opinion, this encapsulates the distinction between authentic tongzigong and contortionism. Most contortionists only emphasize the soft cotton-like aspect. They forsake the hard iron. With the proliferation of martial arts performance tours, tongzigong-derived contortionist acts have been included in less authentic demonstrations. But a trained eye can distinguish the difference. Jin says that an easy way to tell is if they omit erzichan.

Erzichan, or two-finger zen (二指禪) is a classical sequence from tongizong. It is the art of standing on two fingers. According to Jin, this discipline belongs to the iron hard portion of true tongzigong. He believes that real qigong requires strength and that erzichan is one of the more overt expressions of strength in tongzigong. Classic tongzigong is a routine of eighteen different poses including erzichan, but Jin claims that there are actually thirty-six now. Few practitioners can do all thirty-six. Instead, practitioners cherry-pick the strongest methods they can achieve, and construct their regimen from that. In this way, tongzigong is a practice that can be tailored to the individual.

Despite the fact that most of us will never be able to kiss our toes with straight knees or stand on two fingertips, there's still value in the lessons of tongzigong. The preliminary exercises are excellent for building strength and flexibility. When watching a performance of tongzigong, the common audience stands awestruck by its power and grace, the epitome of the human body. Meanwhile, the erudite student of Shaolin makes mental notes on what portions might be integrated into their own practice.

Tongzigong is a demanding discipline. At minimum, Jin Le must put an hour and a half in each day, just to maintain his skills. Frequently, he)ll have to do more. He always begins with at least thirty minutes of meditation. Sometimes he must do more. He must meditate until his whole body heats up. After that, he must do at least another thirty minutes of physical warm ups. After that, he)ll do thirty more minutes of actual tongzigong practice. However, if he gets stuck in one of the methods, he may work for an hour more, just to open that movement.

The worst thing is what Jin calls silian (dead practice 死練). Silian is just going through the motions, just like reciting forms without meaning. In tongzigong, such lapses can be injurious. In Shaolin forms practice, it just makes for lousy kung fu. In this manner, the meditation and warmup is a key to real Shaolin practice, not just for tongzigong, but for all kung fu. When your mind is not clear and focused, there's no way to achieve any Shaolin arts.

| Discuss this article online | |

| Shaolin Special 2010 (May/June) |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2010 .

About

Gene Ching :

Jin Le now teaches at Grandmaster John Leong's Ch)i Life Studio, 2222 152nd Avenue NE, Redmond, WA.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article