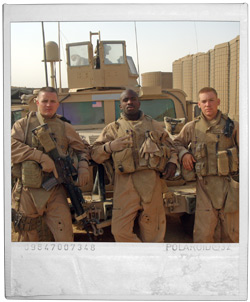

By Robert J. Bibeau, Captain, USMC

September 30, 2008 Al Anbar Province, Iraq

(approximately six miles north of the city of Ar Rutbah)

September 30, 2008 Al Anbar Province, Iraq

(approximately six miles north of the city of Ar Rutbah)

I give commands to the driver of my Light Armored Vehicle-25 (LAV-25), backing him out of our position holding security for the other vehicles in our patrol. A series of further commands and we are creeping seamlessly off a hilltop of little tactical significance, in perfect column formation with the rest of our patrol.

I look to my left and smile as I high-five my young gunner. He is smiling back;; he has just placed a Velcro patch proudly upon his flak jacket. It's torn and stained with sweat and diesel and God knows what else. It's against policy to wear such patches, and I'm violating orders allowing it. But the patriotism of this man compels me to allow it anyways. This patch is our Flag, the symbol of our Nation; besides, it's our "lucky patch." This man joined the Marine Corps barely more than a boy. He joined during time of war knowing full well where he was headed. He volunteered for the Infantry. He volunteered for the Light Armored Reconnaissance community. He was a member of the Battalion during the previous deployment; his courage knows no bounds and neither does his patriotism. No, I won't be the one to taint his sacrifice by making him take it off here and now. Later, when we're safe on a big base, but not here, not in "Indian country."

I point down into the turret and tell him to pick up a scan. He drops, still smiling. I feel the turret jerk and then smoothly turn left. I stand a bit higher to check that my pintle-mounted machine gun is securely locked down. I have missed Iraq and I'm glad to be back. The landscape reminds me of my home in New Mexico. I revel in the nostalgia. It is broken short. I see an amber flash and it is gone in an instant as the front of the vehicle heaves upward. I hear nothing.

I hear everything. Over an intense ringing, I hear everything. I'm confused. Did we just break a strut? Did the driver just blow another engine? Where are the other vehicles going? Didn't they hear it? Where'd all the smoke come from? That smell…it's cordite - spent explosive. I'd know that smell anywhere. Oh my God. IED. Improvised Explosive Device.

Signature Wound

That scene has replayed in my mind countless times. I used to think about it often. And why not? When that bomb

detonated, my life altered forever. I joined the ranks of what has become known as the "signature wound" of

the war in Iraq - a serious concussion resulting from an explosion. Mine was made worse by previous concussions I

suffered as a boxer when I was younger. I ultimately would be diagnosed with a Traumatic Brain Injury, a TBI.

Additionally, as a result of the blast, I suffered a bilateral peripheral nerve injury. Both are immensely painful;

both are horribly misunderstood.

Brain injuries are serious enough, but throw combat into the mix and there is a whole new dynamic. I stayed on the battlefield for another two months before a young corpsman refused to give me any more Tylenol until I saw the medical officer. I expected to be told to take a few more Tylenol and "suck it up." Instead, I was medically evacuated from the theater. By that time my condition had deteriorated significantly. The injury to my brain had caused my speech patterns and cognitive abilities to degrade. My balance was abysmal. I couldn't sleep with any regularity, and I was in constant and at times excruciating pain. It didn't help that I had subjected myself to conditions in which sleeping could be downright dangerous. By the time I was med-evaced, I had been "outside the wire" operating for 43 consecutive days. Staying on edge like that is enough to wear a guy down in and of itsself.

Journey Home

My journey home after being wounded was vastly different than when I came home the first time. Instead of shaking

hands with patriotic Americans after landing in Maine at 3:00 AM, I was surreally saluted by young soldiers and

airmen while disembarking a military transport in Germany. Instead of arriving back to a loving embrace by my wife on a

parade deck full of other happy reunions occurring all around, I was greeted by a pale look of worry and grief on her

face as I lay in a hospital bed in a gown at Balboa hospital. But it was also the beginning of my journey to heal.

As I began the healing process, I attended medical appointments on a nearly daily basis. It was taxing and it was frustrating. Things that had been simple for me before were exceedingly difficult now. I often thought about the day I'd been injured. Despite the constant physical therapy, speech therapy, vestibular therapy, neurology appointments, cognitive studies, MRIs, CT scans, EMG's, and cocktails of various medications, I noticed very little progress. Then one day while reading about how the vestibular system impacts our balance, I remembered something.

During my first deployment I had begun to study kung fu under the tutelage of my friend Chris Nguyen. He had been the medical officer and the battalion intelligence officer at the time. A good friend and an excellent teacher, he had studied Than Vo Dao (a Vietnamese style of kung fu) for most of his life. I remember him remarking once that he was "a double-edged sword. As a doctor, [he] could heal, [his] kung fu could harm, [he] was balanced." I realized I was no longer balanced. If I wanted to heal, I needed that balance back - balance both literally (as a physical result of the injury) as well as spiritually and mentally.

In May of 2009 I began my search for a teacher - though at the time I thought I was just looking for a school. Though I had studied various other martial arts forms over the years, I knew that only kung fu would restore balance to my life. Also, one of the things I had really liked about kung fu while studying under my friend was that many of its applications can be applied while wearing the voluminous amounts of armor used by today's warriors. Not only was kung fu the perfect element to inject into my life for personal development as I recovered, it also served my professional development as a warrior.

Throughout that month I searched for a school. After visiting several schools in my area, I realized that school and location were far less important than teacher. I continued my search into June with little success. With persistent pain, I felt pressured to make a decision on a school. So in desperation I chose a school I had visited but had not been particularly thrilled about. Fate stepped in.

I conducted a map search for "kung fu" on my iPhone. The school I had visited popped up, and mysteriously a location not previously marked appeared just down the street. I thumbed the location, activating a details page that provided me with an address, a phone number and a website. Intrigued, I perused the website, then called the school to ask if I could come down to watch a class and meet the teacher. Two hours later I was at the school.

I noticed immediately that this school was unlike others. Instead of trophies regaling prospective students with past glories, there were books. Instead of photographs of instructors breaking boards or bricks, there was calligraphy and art. This was clearly a place of learning, where intellect tempered the violence being taught. Balance.

Seeking Balance

By late June I had been visiting a physical therapist for months. I was making progress but it was painfully slow.

After going in for an appointment, I would feel good for a few hours. Then I would hurt for days until my next

appointment. During my visit at Shen Martial Arts in Oceanside, Ca, I had noticed that many movements closely

approximated the general movements of my physical therapy. Amazed at how similar the practices were, I thought maybe

kung fu could serve as good spot therapy between visits to the "physical terrorist."

It did not take long to realize that time spent in class learning kung fu was time spent wisely. In class, my pain - and worries - slipped away. For the first time in a very long while, I enjoyed pain-free days - respective to my neck, back, shoulders and arms at least. I was still having headaches due to the brain injury. But at least I could wash away the pain from my body.

Little did I realize that my newfound "therapy" was about to take a new turn, greatly broadening the horizon of my future. In early July I read a magazine about pregnancy. My wife was about five months pregnant, and we were looking for exercises to do together. An accomplished tri-athlete before her pregnancy, she was worried it would take ages to get back to her previous physical condition. Further, we had concerns about delivery complications if she slipped too far. In the magazine, I learned that meditation and tai chi can be very effective.

I spoke to my teacher Sifu Mario Figueroa - owner of Shen Martial Arts - about the matter. He told me he taught qigong as well as kung fu and that it was also effective. I had just recently read a book about Shaolin qigong and I was interested. Later that evening my wife and I attended our first qigong class. That night I slept like a man with no worries and nothing to fear. Instead of waking up in the middle of the night due to pain, I woke early in the morning pain-free, even of my headache.

Qigong Not a Cure All

Since I began my study in earnest, I have learned that kung fu and qigong are not a cure-all that I can drink at

ten, two and four. I have to work hard to reap the benefits. As I learn more and continue to heal, improvements are

not as dramatic or easy to come by as they initially were. Still, my constitution is stronger, and missing a class no

longer condemns me to a night of pain. If I should have pain on a given day, I can simply find a peaceful place in my

house or backyard and work through a warm-up and the ng lung ma of Choy Li Fut or what I have learned of

qigong's Lohan - thus conducting my own spot therapy and improving my immediate condition.

My professional life has also benefited, as I have seen improvements that will soon have me back to work. I recently began running again and have achieved distances of just over six miles - a modest number, compared to other infantrymen or what I could do prior to the injury, but an accomplishment nonetheless.

I have also found a path to regaining my spiritual balance. The values a kung fu student learns - especially when consciously aware of the Tao - are entirely compliant with the intrinsic "core values" of honor, courage and commitment embraced by our marines.

After that IED exploded, my driver got us clear of the kill zone, and it was at that time that we spotted seven military-aged Iraqi men dancing in celebration. Though they were over half a mile away, I could clearly see them through a powerful sight. It seemed obvious enough that some or all of them were guilty of the attack. I was angry, and the base impulse was to kill; but what is a life of service and sacrifice if a warrior gives way to base impulses? Dancing is not a hostile act, nor is it a hostile intent, and it certainly doesn't warrant death. It is inspiring to think that men in ancient China knew this to be true as well. Seeing my teacher teach these timeless values to young students is humbling.

No warrior ever sat behind a rifle with a target lined up in his sights and thought, "Hmm, what do my "core values" tell me to do in this situation?" A warrior is shaped by a lifetime of experiences, but he must always maintain a sense of right and wrong when it comes to taking a human life. This "sense" is present when he pulls the trigger on an individual clearly planting and IED at a known previous IED site, and it is equally present when he does not pull the trigger on a rapidly approaching car that doesn't see the patrol because the sun is in the drivers eyes - even though the warrior could have pulled the trigger without question because it "might" have been a car bomb. The values of kung fu and the Tao are not only compliant with the ethos or today's warrior, they are intrinsically linked.

The Way of the Warrior

Beyond physical fitness, studying kung fu has helped me develop professionally in other areas as well. I have found

parallels between kung fu and the warrior ethos to which I have dedicated the past 10 years of my life in the Marine

Corps. These parallels exist across the spectrum of requisite warrior skills from warrior virtues to actual combat,

from proper nutrition to proper sleep and rest habits.

MARINE CORPS DOCTRINAL PUBLICATION 1, WARFIGHTING defines the essence of war as "a violent struggle between two hostile, independent, and irreconcilable wills, each trying to impose itself on the other." Ultimately war is a clash of wills characterized by violence. Is this concept different than a person defending himself or loved ones out of immediate necessity for a violent response? The argument could be made that all martial arts teach this precept. But I have found something unique to other martial arts within kung fu. WARFIGHTING elaborates on the definition of war by asserting that "war is thus a process of continuous mutual adaptation, of give and take, move and countermove."

Further, WARFIGHTING tells us that it "is critical to keep in mind that the enemy is not an inanimate object to be acted upon but an animate force with its own objectives and plans." Whereas other martial arts I have explored assert that one should "not think, simply react" or should "allow instinct to take over, to dominate actions" in combat, kung fu asserts that one should "be in the moment" - that is to say, be aware of both what you are doing and what your enemy is doing. Or as one of my mentors drilled into my head as a young lieutenant: to "think through the tactics of what you are doing."

The bridge between kung fu as a "sport" and a skill-set worthy of true "warriordom" is made evident by a vast array of similarities that may take me a lifetime to fully explore. However, as a means of "scratching the surface," there are a few immediate issues worth mentioning.

The principle of redundancy. One of the first things a student of kung fu learns is that the best way to avoid a punch is to "not be there" when the punch arrives. Why simply block when you can just as easily move, strike the enemy's incoming blow and deflect it? Why strike an enemy once in the face when you can simply sau and hit his arm, face, neck and clavicle all with one blow? This principle of redundancy is likewise utilized throughout combat actions and planning within the Marine Corps. If during an attack I intend to shift the impacts of suppressive fire of my machine guns from one target to another (thus allowing a constant barrage of fire oriented on the enemy while my maneuver elements close with the remaining enemy at the original target), then I am not going to plan for this action by simply making a call over the radio. Radios fail, so why not build into the plan an additional way to communicate with those machine gunners? Why not launch a clearly identifiable flare? Redundancy is simple and effective; it is part of both the art and science of war, and the art and science of kung fu.

The principle of efficiency. Kung fu is, by its nature, very efficient. Why block an enemy's strike when you can use the inertia of his own blow to turn his body, thus creating a clear opportunity for you to end the violence much more quickly? Why apply significant force to stop a kick with a tae kwon do down-block when a small amount of energy delivered via a quon kiu is enough to deflect the kick, again creating opportunity for you to deliver your own strikes (for instance, a kwa chop efficiently delivers enough force to turn the balance of the fight in your own favor). This principle of efficiency is comparable to a war-fighting principle known as "economy of force" - the idea being that one should not waste resources in war or conflict. Why should a commander commit a large force to an action when he can achieve the same decisive action at a given point with a much smaller force? This is not to say that economizing or achieving efficiency means to never apply a significant amount of force; it simply means to use what is necessary.

The principle of surprise. The "element" of surprise is perhaps the best-known fundamental of war-fighting. Its necessity has been written about by scholars and warriors and employed by warriors and governments for thousands of years. According to Mao Tse Tung, "War demands deception," and he was paraphrasing Sun Tzu. Surprise and deception are intrinsically linked, and they can be performed by individual warriors on a battlefield or kung fu practitioners when necessary. I am reminded of a story my friend and former Platoon Sergeant once told me about a gunfight he was involved in, in Ramadi, Iraq. He had seen a few Marines dart across a street, and as they did so, an enemy rocket detonated near them. Thinking the Marines were dead, he continued to engage the enemy to allow time for the dead and injured to be rescued. While clearing a jam in his machine gun, he saw one of the Marines move and realized they were alive. He began to yell to them while re-engaging the enemy. My friend said he would never forget their response. "Hey Sergeant. Shut up! They think we're dead. Keep shooting, we'll get across." Individual warriors engaged in opportunistic deception to enable Marines to cross the street and get around the enemy's side, turning the fight on that street. Is this deception and ensuing surprise so different from the kung fu student's execution of a lung mei followed by a snap kick? The enemy is deceived, perceives his own opportunity and steps into a vicious assault he could not see coming and cannot likely recover from.

These are but a few examples. Two other simple examples draw an uncanny link between actual combat and kung fu, showing that what the ancients developed remains a viable warrior skill. The first is "maneuver warfare." While with kung fu you may not try to "out flank" the enemy, you are always assessing the enemy's strengths and weaknesses - in military jargon, his "surfaces and gaps." Both the kung fu practitioner and the warrior seek to identify the locations or abilities of an enemy to avoid, and the locations that may be exploited to the enemy's detriment. Both seek to topple the enemy's "center of gravity." Both seek decisive action to achieve victory more quickly. Both recognize that combat is chaotic and uncontrollable and therefore one must be fluid and adapt, rather than be rigid and unwavering. The final example addresses the practical use of kung fu on today's battlefields.

In 2007, I served the majority of my first deployment as our battalion's intelligence officer. I can say with certainty that "fourth generation warfare" (in lay terms, large conventional forces engaging non-conventional and typically non-governmental combative elements) often finds it not only more effective but often critical to detain an enemy rather than kill him in order to gain information. As a result, warriors often find themselves in close quarters with the enemy during combat operations in a COIN (Counter Insurgency) or Fourth Generation Warfare environment (COIN and Fourth Gen War are not always synonymous.)

Consider for a moment the tremendous amounts of weight our warriors carry into battle today: a flak jacket with heavy-armor "SAPI" plates (effective but heavy nonetheless), weapon (anywhere from 7 to 22 pounds for your organic "line platoon"), ammunition (minimum 120 rounds for a rifleman, much, much more for a automatic rifleman), grenades and other high explosives, helmet, water, food, night vision goggles, batteries, flashlight, gas mask, day and night ballistic eye protection, bayonet, multipurpose tool (Leatherman or similar), weapon-cleaning gear, map, compass, and first aid kit. This is the typical "load out," and it is very heavy. Some of it may not sound like much, but it adds up, and pretty soon you're carrying 80 pounds or more and that's your fighting load. So consider trying to actually go "hand to hand." All that cumbersome weight curbs the stability and range of motion of a kung fu practitioner. You may not be able to execute an MMA-style single- or double-leg takedown in that armor, but you can certainly throw a vicious sau. Such practical applications are what keep kung fu relevant on today's battlefields.

Kung fu is an effective means of staying physically, mentally, morally and ethically fit. It is also - despite its sometimes flowery and superfluous looking nature - an extremely effective fighting style applicable to real combat. This capability is tempered and nurtured by the values inherent in the system of kung fu.

Experiencing actual combat is not what defines a warrior. Conversely, unique fighting abilities or talents do not automatically make a warrior. Fighting an opponent in an Octagon, where there are rules, safety equipment, and an unbiased party ready to stop the fight if it gets too dangerous, does not make a man a warrior - no matter how talented a fighter he may be. It makes him a sportsman. A warrior takes action directed and defined by the morals and ethics driving his decision-making engine, regardless of where his profession may place him - be it a battlefield, an octagon, police cruiser, desk, or political office.

| Discuss this article online | |

| January/February 2010 issue |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2010 .

About

Robert J. Bibeau, Captain, USMC :

Captain Robert J. Bibeau studies kung fu and qigong under Master Mario Figueroa at Shen Martial Arts,

1680 Ord Way, Oceanside CA 92056. shenmartialarts.com.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article