By Gene Ching

Clad in traditional Daoist robes, Zhong Yuechao looks like he just walked off the set of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. While Americans are familiar with robed Buddhist monks like the Dalai Lama, Daoist attire has a distinctly Chinese flair, yin black and yang white accentuated with an assortment of dark-hued blues. Instead of shaven pates, Daoists let their hair grow with the flow. It's long and uncut, tied in a top knot with a signature dragon hairpin. To top it all off, Daoists customarily don traditional hats which are unlike anything seen in the West. The overall appearance is dramatic, as if an immortal hermit mystically escaped from a Chinese painting.

Clad in traditional Daoist robes, Zhong Yuechao looks like he just walked off the set of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. While Americans are familiar with robed Buddhist monks like the Dalai Lama, Daoist attire has a distinctly Chinese flair, yin black and yang white accentuated with an assortment of dark-hued blues. Instead of shaven pates, Daoists let their hair grow with the flow. It's long and uncut, tied in a top knot with a signature dragon hairpin. To top it all off, Daoists customarily don traditional hats which are unlike anything seen in the West. The overall appearance is dramatic, as if an immortal hermit mystically escaped from a Chinese painting.

As a Wudang priest, Zhong Xuechao (鍾學超) always wears Daoist robes as an expression of his practice. Zhong, who also goes by Master Bing, is now teaching in Los Angeles, but in the City of Angels his unique apparel barely attracts a second glance. "There's less staring in America than in China," says Bing in Mandarin. "They don't see many Daoists from the mountains in China. In Los Angeles, most people don't ask. There's plenty of unusual stuff there. Sometimes people ask me where I bought my outfit ? Chinatown? I tell them I got it from China."

Master Bing stands among the first pioneer Daoist priests from Wudang to come to America. While Chinese kung fu masters have been in America for decades and Shaolin monks have been immigrating here since the early '90s, genuine Wudang devotees are just beginning to arrive. The Wudang community is smaller than those others, but just as outstanding and not just because of the way they dress.

Respecting Wu

"America doesn't know Wudang," observes Bing. Nevertheless his outfit is regarded with some esteem. Bing is often treated as a man of the cloth. He finds himself answering questions about spirituality and discipline, all asked reverently. "They seem to feel I'm more religious ? more like a Western priest ? instead of Daoist. I recently mailed a sword and the people at the U.S. Post Office took such good care. They felt it was very precious. Maybe the quality of service is better in America, but I feel the respect."

Bing first journeyed to America in 2002 for a week-long visit. He was part of the five-member entourage of Zhong Yunlong, the Chief Priest at Wudang. It was the first Wudang delegation to grace America. Propitiously, 2002 was the 10th Anniversary of this magazine. In celebration, we held a Gala Benefit for the U.S. Olympic Wushu Team. The Beijing Olympics had just been announced, and we were all hopeful that wushu would be the next new Olympic event. Chief Priest Zhong was a guest of honor at that Gala. He was the only master permitted to demonstrate in our coveted Cover Masters showcase who had not previously graced our cover. We rectified that the following year by featuring Zhong on the cover of our September October 2003 issue. It was America's first real glimpse of an authentic Wudang priest.

During Bing's short stay, he was struck by the freedom we Americans enjoy here. These freedoms were more personal than political, like the informality with which children address their parents. Chinese philosophy stands upon three pillars: Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism. Confucianism establishes a rigid social hierarchy where students bow to masters and children bow to parents. Overhearing some children addressing their parents by name instead of a formal title was a little shocking to Bing. Nevertheless, he was impressed by the atmosphere of freedom and hoped to return to America someday.

When he went home to Wudang, the tourist industry was growing. Wudang enjoyed an economic boost from a spike in tourism in the wake of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Bing found himself escorting many American guests around China's mystic mountain. It was a sharp contrast from his short experience in the States. "Life at Wudang Mountain is peaceful," recounts Bing. "We study the Daoist canons and practice kung fu. It makes you focus, slow down the pace, and not live to be so busy and material. We chant in the morning and evening. In some rituals, each character from the canon is chanted for a minute. We chant for at least half an hour a day."

Daoism is one of the most misunderstood traditions in the West. Difficult to categorize into a western box, it vacillates between a philosophy, a religion, a folk custom and shamanism. Ancestor deification, communion with nature and the quest for immortality are all major elements. It is from Daoism where we get the concept of taiji, not just as a martial art but as a cosmological paradigm. Traditional Chinese Medicine, Feng Shui, the Chinese Zodiac and even Chinese food are all deeply rooted in Daoism.

Part of what makes Daoism so elusive is that it is a reclusive tradition. Many of its proponents are hermits living in seclusion in the dense mountain regions of China. This is why mainland Chinese rarely see Daoists in traditional garb. And unlike Buddhism, which originated in India and then spread through China and the rest of Asia to evolve into Zen, Daoism is uniquely Chinese.

Today in America, Bing confesses he no longer chants quite as much as he did at Wudang. But he often carries a photo album of Wudang scenery to share with people he might meet. Wudang is one of China's most spectacular natural resources and a UNESCO World Heritage site. "That creates some envy. I tell them we practice seven to eight hours a day at Wudang. Most can't do that. But they still want to visit."

Wudang versus Shaolin

According to Bing, there are 108 Wudang priests and nuns at Wudang. In China, 108 is an auspicious number. This is reflected within the martial arts, such as the 108 movements of the Yang Tai Chi long form or the 108 Wing Chun wooden dummy techniques. It also appears in Korean Kuk Sul Won in a form called paek pal ki hyung and in Goju-Ryu Karate in a form called suparinpei. Both titles translate into 108. The origin of the number is unclear but martial numerology echoes universal Asian cosmology. Buddhists carry sacred necklaces called malas with 108 beads. In Daoism, there are 108 sacred stars. And in Hinduism, Nataraja's celestial dance has 108 steps. As a bastion of Daoism, Wudang's membership stands at 108 by the most cosmic of means. "It happens just naturally," says Bing nonchalantly.

Shaolin Temple maintains a brotherhood of warrior monks called wuseng (武僧). While almost all Shaolin monks practice martial arts, wuseng focus strictly upon preserving the Shaolin's precious martial legacy. Our previous issue was our annual Shaolin Special. Inside that issue, Shaolin's abbot Venerable Shi Yongxin stated in interview that there are currently 280 monks and 20 nuns. That figure does not include wuseng. The size of the wuseng population is unclear. Bing says Wudang has a similar class of adept focused strictly on martial arts called wudao (武道). He estimates that there are about ten or twenty wudao now, but they are included within the 108. He also notes that the wudao are not differentiated from the other Wudang practitioners until they come down off the mountain.

In the surrounding mountains, Bing estimates there are ten to fifteen private martial arts schools. Most of these are run by secular wudao. There is also an official school that belongs to the Daoist association. On the mountainside across from Purple Cloud Temple stands the Wudang Daojia Wushuyuan (武當道家武術院), a martial arts school that belongs to the Wudang Daoists. Zhong Yunlong was the former headmaster there. Bing isn't sure, but guesses that there are over 500 students training at Wudang now. Again in our previous issue, it was reported that Shaolin has 68 officially-registered private schools and a student population of 58,000.

Currently there are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of Shaolin monks scattered across the globe. Most of them are wuseng. The San Francisco Bay Area alone is home to over three dozen Shaolin graduates. As for Wudang priests abroad, there are only a very few.

An America Eagle, a Chinese Snake and Turtle

In 2007, Bing returned to America and taught some in Colorado. The terms of his visa were limited, requiring him to go back to Wudang for a spell, but he recently returned and is now in southern California. While Colorado was more mountainous like Wudang, southern California is more of an adjustment. "It's very dry," says Bing. "Wudang is very comfortable." L.A. is also inconvenient because Bing doesn't drive. He must rely on buses, students and friends to go anywhere. "At Wudang, if I want to go anywhere, I just hike the mountain. Here, it's just cars and buildings." Here Bing breaks from Mandarin and tries practicing his English. "It's different, but I can get used to."

What's even more challenging is teaching. On the mountains of Wudang, Bing's students practice all day, every day. There's not much else to do apart from hike the mountain, so students don't have many distractions. And Wudang is steep, so the daily process of getting around by hiking alone is better exercise than most people get in L.A. "I feel on the mountain, the students can get good. I see a future for them. With only one or two hours a week, two to four hours a week, they can't get good." Nevertheless, Bing works hard to transmit Wudang wisdom in America. And in a mystical twist of fate, he's found a pivotal teaching role amongst the original Americans.

"Los Angeles is the Native American capital of the country," states Marcos Aguilar. Aguilar is one of the founders and an active administrator of Academia Semillas Del Pueblo, a kindergarten-through-twelfth charter school that provides public education based upon Indigenous culture. The student body is largely comprised of Mexica, Purepecha, Vapoteca, Navaho and Apache descendants. According to Aguilar, outside the reservations, many indigenous peoples have congregated in the greater L.A. area, especially those from Central America.

Aguilar is also a practitioner of Yuen Kay San and Sum Neng branch Wing Chun kung fu under Master Tom Wong, so he's connected to Chinese martial culture. As part of the school's international studies program, the school is connected to Hanban, a non-governmental and non-profit organization affiliated with the Ministry of Education of China. Several students have participated in exchange programs through Hanban, allowing them to study in Beijing and Hubei. Aguilar travelled to China with two students and three other teachers to explore possibilities of developing a sister school in China. That journey took Aguilar to Wudang.

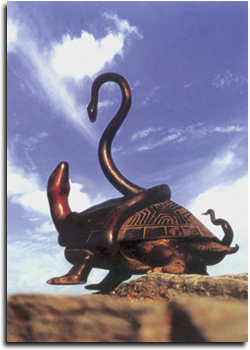

Aguilar was awestruck by what he found at Wudang. The natural wonder of the mountains and the rich martial heritage makes for an inspirational journey for any practitioner artist. But it really hit home when he ascended to the top of Wudang's peaks and saw its symbolic totems ? the turtle and the snake. According to legend, Zhen Wu (the namesake Daoist patriarch of Wudang) once meditated so long that his stomach growled. The sound disturbed his meditation, so like Bodhidharma, who cut off his eyelids after falling asleep in practice, Zhen Wu tore out his stomach and intestines. Bodhidharma's eyelids sprouted into the first tea plants. Zhen Wu's digestive system transformed into a turtle and a snake, spirit animals to guide him along the way. "The turtle and snake are powerful symbols in our (Native American) culture," comments Aguilar. "It reaffirmed the cultural connection."

Aguilar was awestruck by what he found at Wudang. The natural wonder of the mountains and the rich martial heritage makes for an inspirational journey for any practitioner artist. But it really hit home when he ascended to the top of Wudang's peaks and saw its symbolic totems ? the turtle and the snake. According to legend, Zhen Wu (the namesake Daoist patriarch of Wudang) once meditated so long that his stomach growled. The sound disturbed his meditation, so like Bodhidharma, who cut off his eyelids after falling asleep in practice, Zhen Wu tore out his stomach and intestines. Bodhidharma's eyelids sprouted into the first tea plants. Zhen Wu's digestive system transformed into a turtle and a snake, spirit animals to guide him along the way. "The turtle and snake are powerful symbols in our (Native American) culture," comments Aguilar. "It reaffirmed the cultural connection."

When Aguilar returned to America, he was perusing the newsstands and found the previous article published on Master Bing in our magazine. Eager to make contact, he followed the lead to Colorado, only to discover that Master Bing was currently in Southern California. Aguilar contacted Bing immediately. He asked Bing to come teach Physical Education to the students and help develop some of the faculty into coaches. "I teach them kung fu basics," say Bing. "Someone taught the Taiji 24 form to them a few years before I came, so there was already some foundation."

The Conqueror of All Things

Daoism has much in common with many Native American beliefs. Both traditions share beliefs in animism, the power of healing, the study of herbs, storytelling, fortune-telling and vision-quests. The roots of Daoism lay in ancient Chinese Shamanism. The term "shamanism" is commonly used to describe Indigenous spiritual practices, so much so that many even believe "shaman" is a Native American word. But its origin is Mongolian. It means "person who knows."

Some postulate that there was a lineage transmission of Daoism to America, perhaps via prehistoric immigrants over the Russia-Alaska land-bridge or pioneer Chinese explorers like Zheng He. Those theories are dubious at best. It's more likely due to parallel development of universal concepts. Compassion, moderation, healing, humility and a connection to a spirit greater than the material world speak more to the human condition than can be divided by the sea.

Whatever the case, Bing feels the connection. "I've watched their sun dance ceremony and it reminds me of Daoist rituals. It's simple music, very plain and down to earth." Aguilar agrees. "In many ways, Daoism speaks of the same things we do ? of harmony and following nature. In L.A., that's a huge oxymoron." Indeed, few places could be farther from L.A. than Wudang Mountain or the pre-European America of centuries ago. Nevertheless, Aguilar and Bing work together towards the same goal ? to inspire the next generation to carry the torch of their time-honored traditions into the future.

"Bing's contribution to our school has been immense," continues Aguilar. "He was like an icebreaker in our community. It was hard to convince the families something Chinese should be part of our curriculum at first, but when they saw what their kids could do ? the kung fu ? they got excited. Martial arts was the gateway." Pop culture pigeon-holes the martial arts into self-defense, kung fu flicks and MMA. Many people hold stereotypic notions of Indians as villains in cowboy movies, and who knows what reaction a robed Daoist priest might draw? These caricatures are horribly limiting. They fail to encompass the full potential of these venerated traditions. Here, Wudang bridges the gap between different cultures. Instead of fighting, it's uniting. A connection is made between people from opposite sides of the world and each becomes stronger and wiser from that union. In this way, the martial arts serve as a gateway to world peace.

According to the Dao De Jing:

"Fate does not attack, yet all things are conquered by it;

It does not ask, yet all things answer to it;

It does not call, yet all things meet it;

It does not plan, yet all things are determined by it."

When the paths of Master Bing and Marcos Aguilar crossed, it felt almost predestined. Daoists have tremendous faith in the auspicious and the natural flow of events. The opportunity to share with the young students at Academia Semillas Del Pueblo was not at all how Bing imagined his American students to be, but fulfilling nonetheless. For Bing, being able to transmit his Wudang culture to America is a duty and a privilege. The Dao works in mysterious ways. Once again, Aguilar agrees. "Things happen to us for a reason."

| Discuss this article online | |

| March/April 2009 Wudang Special |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2009 .

Written by Gene Ching for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article