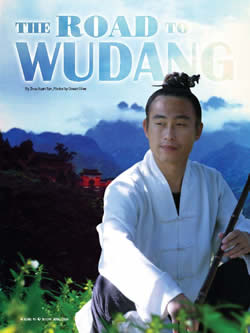

By By Zhou Xuan Yun (Mysterious Cloud)

I was born in the year of the monkey in a small village in central China's Henan Province. My grandparents had moved there after floods had destroyed their hometown. Because we were not native to the village, my family endured a lot of bullying. The locals made sure my parents had to use the worst land for farming, and the worst spot for building our house. When I was in fourth grade my grandfather fell ill, and because we needed money for hospital bills, I had to leave school. I worked on our farmland, helping my family plant corn and cotton. Eventually, my parents decided to send me to Wudang Mountain to study martial arts. I was a very active child, much harder to contain than my brothers. It was also my parents' hope that if a member of the family were good at martial arts, the local villagers wouldn't bully us. As a boy, I used to walk for hours to watch kung fu movies on the sole TV in the area. I was always fighting with my brothers in our family's front yard. So, when my parents asked if I'd like to go study, I readily agreed. My father managed to borrow some money from a distant relative, and we headed out on a two-day tractor, bus, and boat trip that took us to Hubei Province.

I was born in the year of the monkey in a small village in central China's Henan Province. My grandparents had moved there after floods had destroyed their hometown. Because we were not native to the village, my family endured a lot of bullying. The locals made sure my parents had to use the worst land for farming, and the worst spot for building our house. When I was in fourth grade my grandfather fell ill, and because we needed money for hospital bills, I had to leave school. I worked on our farmland, helping my family plant corn and cotton. Eventually, my parents decided to send me to Wudang Mountain to study martial arts. I was a very active child, much harder to contain than my brothers. It was also my parents' hope that if a member of the family were good at martial arts, the local villagers wouldn't bully us. As a boy, I used to walk for hours to watch kung fu movies on the sole TV in the area. I was always fighting with my brothers in our family's front yard. So, when my parents asked if I'd like to go study, I readily agreed. My father managed to borrow some money from a distant relative, and we headed out on a two-day tractor, bus, and boat trip that took us to Hubei Province.

In 1994, the only martial arts school actually located on Wudang Mountain was the Wudang Daoist Association School. We lived and trained at Purple Cloud Temple under Zhong Yun Long. He trained with Guo Gaoyi and Zhu Chengde and had spent three years traveling around China, searching out the Wudang practitioners who had gone into hiding during the Cultural Revolution. The tuition at that time was about 1,200 yuan per year, about $170. In addition, we had to pay 25 yuan per week for food. Though it doesn't sound like much, it was difficult for my parents to pay so much money. I was by far the poorest student at the school. I remember that when I got there all I had was one worn-out pair of pants, not suitable for training in. I also didn't have a plate to use at mealtime. Lucky for me, the other students were kind and gave me what I needed. By my second year at the school, I had proven myself as a serious student, and my tuition was waived.

When I first arrived at the school, there were over 40 students. Being 13, I was among the youngest. Most of the students were around 18-19 years old. There were also several middle-aged people and older adults who mostly studied taiji. In my third year there, two 13-year-old girls from Sichuan Province also came to study. The two girls got their own room, which we envied greatly. Us boys were 12 to a room. Many students also complained about the food. In Henan, where I'm from, the staple food is noodles. But, in Hubei Province, they eat rice. I remember that when I got to Wudang Mountain, I hated eating rice. I found it hard to digest, and felt nauseous for weeks. I also wasn't used to eating meat. On our farm we had animals, but they were all sold in the markets. We ate meat maybe once a year. At Wudang we had meat three times a week. Many people found the lifestyle difficult to adjust to. Out of the 40 original students that were there when I entered the school, only 20 returned the next year. By the third year, there were less than 10 of us remaining. I think it is safe to say that at Wudang Mountain, for every 200 students who train there, maybe one or two end up sticking it out.

The Way of the Student

The practice was very bitter. We would wake up at 5 am and begin by working on our flexibility. For about half an hour we would practice splits and other stretches. I remember we would fall asleep while in splits. After stretching we would do some basic conditioning: standing in horse stance or doing push-ups. We would stop for breakfast at 7 am, and at 8 am begin the stretching and conditioning all over again. We would also drill basic kicks and punches. The older students, who stood on the sidelines with thick wooden rods in their hands, supervised our morning practice. Their favorite thing was to find one of us slacking. We had class seven days a week. But, we always had a vacation during the Spring Festival. Also, sometimes when they saw that we were exhausted, we'd all be given a day off.

I remember that on my third day, my legs were badly swollen from over-exertion. But, of course, I had to keep on practicing. That night, I was so tired that I couldn't raise my legs to get into bed. I had to lift them with my hands. I was still pretty young at the time, and would sometimes cry at night. The winter was the worst. In addition to training, we had to go collect firewood on the mountain. Every student had to collect 30 kilograms of wood each day. I will never forget the day when I was so tired while collecting firewood that I fell asleep in the snow. But when I woke up, there was a pile of firewood next to me. An older student had collected it for me.

After three months of conditioning, we started learning our first form. It's a short combination of the basic punches and kicks. Nowadays when I teach, most of my foreign students feel satisfied with it after about a week; but when I was learning, we drilled the form to perfection, practicing it for more than six months. To this day, I feel that of all that I've learned, those basics are the most important. But at first, I was too young to appreciate what I was learning. While I was used to hard work, having grown up on a farm, I often got very homesick. So, towards the end of the first year I decided to run away. I made it all the way home, but when I got there, my father yelled at me and sent me back. Of course, when I got back, I got yelled at again.

By the second year, we had become more mischievous. Every morning all of the students would jog up the mountain together as a group. Sometimes, my friends and I would wait until the people in front of us weren't paying attention, and then leap off the path and into the woods. We'd sleep in the woods until we heard the group pass by on their way back down. Right after they passed we'd crawl out, and run after them. Not that we didn't get caught. Usually they'd make us stand in horse stance. A few times I had to stand in horse stance all morning, holding a really big rock. But to a 15-year-old boy, it was worth it for the extra sleep. Sometimes we had to jog wearing heavy sandbags. I remember that on the way out all the students would find flat rocks, and pour the sand out, only to later fill the sandbags up again on the way back. We were like robots in those days. Eat, practice, sleep, eat, practice, sleep? Many people found the lifestyle difficult to adjust to.

It wasn't until the third year that I started to find the training interesting, and started to train harder because I was genuinely interested in it. I liked the changes that were happening to me ? not just physically, but mentally as well. In the third year, I started to help teach the younger students. With a handful of advanced students, I trained in all of the traditional Wudang martial forms: first Xuan Gong Quan, Xuan Wu Quan, Xuan Zhen Quan, Taiji, Xingyi and You Long Bagua. Northern external styles, like Shaolin Quan, contain many flips and jumps. These types of moves are easier for young people, but as people age, the strength and dexterity that the external arts require will gradually fade, and they will no longer be as capable of the more acrobatic moves. The Wudang forms, by comparison, are more grounded to the Earth. This is also why we stand with the chest slightly concave and the back rounded ? to develop the alignment to guide incoming force downward into the Earth. Wudang stances are long and deep, which also develops a strong root. Plus, many of the low stances used in the Wudang forms are used to step behind a person, to create something for the opponent to fall over. These arts are very practical; using everything available to you to fight the opponent, including the opponent's own strength.

The Wudang styles are "internal" martial arts, meaning that they focus on flexibility, whole body movement, and increased qi flow in the body. In the internal arts, the practitioner does not rely on the use of brute strength to defeat the opponent, but instead uses muscular strength supported by qi. The Wudang martial arts practice exerting force only when already in contact with the opponent, by transforming and redirecting the attack. You can see this philosophy in what Lao Zi wrote in the Dao De Jing saying, "The soft and the pliable will defeat the hard and strong." By learning exactly when to apply force, and in which direction, we learn to redirect an opponent's own weight and momentum, using it against them, attacking when the opponent is off balance. For example, say I am fighting someone stronger than I am: if I push them with 30 pounds of force, it may not knock them over. However, were I to pull the person forward slightly, they then would naturally react by throwing their weight backwards, at which time we stick, follow, and attack. You may also just wait until the other person is moving backwards. Were I then to apply the same 30 pounds of pressure, with the two forces combined, it is more likely that the person will fall over. It is very efficient! In my opinion this is the reason why internal arts are the best choice for women, small-framed people, and older people. You can learn how to most effectively use the physical strength you have, while developing these subtle skills of listening and following jin, and defeat an opponent without having to overpower them.

The principles of the internal arts can also be applied to weapons. My favorite weapons have always been saber and whip. We also learned staff, knife and sword. That was the year that the performance troupe was formed. I was picked for the troupe and often had performances, including some in front of a foreign audience. Several years later the performance group toured China, and even performed overseas.

The movements of the internal arts are often compared to clouds and water. Clouds move seamlessly. Water absorbs any force that comes at it, and flows around obstacles. Water is actually one of the most common metaphors in Daoist literature. The Dao De Jing, Chapter 78 reads:

- Nothing in the world

is as soft and yielding as water.

For attacking the hard and rigid,

nothing can surpass it.

The soft overcomes the hard;

the gentle overcomes the rigid.

Everyone under heaven knows this to be true,

But nothing else is as capable.

Observing nature and learning from it is common ground for Daoism and the martial arts. Because every aspect of life is a manifestation of the Dao, even a cloud or the movements of an animal can teach us something!

Following the Dao

During my years of training, my interest in Daoism was also growing. My teachers at the martial arts school never talked about Daoism. However, we would often come into contact with the monks who shared the mountain with us. For me, Daoism is a way of living in harmony with nature. It is a way of putting each of my actions into perspective and seeing which of my actions run contrary to nature and are thus unhealthy. As the martial arts helped me attain physical health, learning about Daoism brought about mental and spiritual well-being. In 1997, I decided to become a Daoist monk. In all my years at the martial arts school, I was the only student who chose the Daoist path. Even then, Daoist monks were few and far between. When I took my ordination as a monk, I moved to Jin Ding temple, which is at the very top of Wudang Mountain. I learned how to recite scripture, learned various practices, and studied the I Ching. At night after the tour groups left, I practiced my martial arts.

It is an ancient Daoist tradition to travel from temple to temple in order to learn new things. So, in late 1999, I left Wudang Mountain. Because Daoism teaches that spiritual health is linked to physical health, many martial artists can be found in Daoist temples. Whenever I came across a fellow martial artist in my travels, I would take the time to learn what I could from them before moving on. I traveled through Henan Province to Tanghe where I worked teaching at a martial arts academy that one of my fellow students had started. I spent some time at Hua Shan, a famous Daoist mountain outside Xi'an. I also spent some time in the temples of Shandong Province, at Tai Shan and Lao Shan. While at Lao Shan I met two Daoists named He Zhen Wei and Leng Song Yi, who had also studied Bagua and Xingyi. The three of us became good friends, practicing and exchanging ideas together. The three of us traveled together to Zhou Kou in Henan where I had a chance to meet their teacher, a layman named Zhang Ming Liang who told me the story of how he had learned martial arts from a teacher named Zhang He Nian. Zhang Ming Liang explained to me that, when Zhang He Nian was young, he had come in second place in a national tournament that was held around the end of the Qing Dynasty and had served as president of the Henan Province Martial Arts Association before he passed away.

After this, I continued traveling, spending some time at Jiugong Shan in Hubei Province, before settling in 2004 in Yunnan Province where I live today. Yunnan Province is one of the most naturally beautiful places in China, and so, many foreign people travel here. Initially, I had planned to focus on my own practices, but some of my foreign friends asked me to teach them, so I started offering classes. I have been able to teach students from many different countries. My students tell me that I am not what they would consider a traditional monk! I think that they are confusing us Daoists with Buddhist monks, but we're really quite different! The sect of Daoism that I was ordained into, which is called the Orthodox Unity lineage, does not teach that the sensual world is an illusion. The illusion, I think, arises when you confuse your preconceived notions of how things should be with what is really there. I feel that man's natural desires are in harmony with the spontaneous processes of the universe. While teaching in Yunnan, I met my wife, and now we have a young daughter. For me, having people with whom I can share my life has been an incredible gift. My daughter, especially, is a wonderful teacher. She's so pure and spontaneous! Because my English is very basic, my wife helps me by translating the things I write and teach. Because of this, I was also able to travel to the United States last year.

Journey to the West

Even though I have taught many foreign students, I was still very surprised to see how popular the martial arts are in the West. Almost every town we passed through had a martial arts school of some kind. My wife says that it is because of the popularity of martial arts movies. I have heard from my friends still at Wudang Mountain that tourism there has increased significantly since the release of CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON. In China these days only a very small percentage of young people practice the martial arts. Students have a very stressful life, and often are kept at school until the evening. It is now very rare for a young person to devote themselves to the traditional arts. In many ways, the focus of the martial arts in China has shifted. With the increase in competitive wushu, more people are concerned with the beauty of the movements than with their functionality. Visually impressive movements draw a crowd and work well in competition, but they often break with wugong's strong practical roots. This is not helped by the tourist industry. Because temples are quickly adopted as tourist landmarks, the monastic lifestyle has adapted to incorporate increased cash flow and publicity.

It is only among retired people that the martial arts are flourishing in China. Every morning the parks are filled with older people practicing taiji and qigong. Perhaps it is due to this imbalance in the age of practitioners that the taiji being taught in the west looks less martial and more like the health-preserving art practiced by our older generation. Being an internal art, taiji is a great health practice. But, I am afraid that taiji is losing touch with its roots as a fighting art. Even for people not interested in learning how to fight, learning the martial applications for every move would help them remember the form, and to practice each move correctly. I think that for many people in America, broadening their taiji practice to include more of the martial side would make their practice more rewarding. I intend to preserve and promote the martial aspects of the Wudang arts.

Where the Road May Lead

For centuries, the secrets of Wudang Mountain were available only to very few people. But what was started at Wudang is now spreading all over the world. I am fortunate to be a part of this process. I have been able to travel and teach workshops, and be a part of several documentaries. This summer I will be recording a series of teaching videos in the U.S. with Yang's Martial Arts Association Publication Center, and teaching classes in Boston. I have many ideas for things I'd like to do in the future. I'd love the opportunity to teach more in the West, or bring groups of people to visit China to study. We have a saying in China: "You only realize how valuable your treasure is when you see someone else holding it." Hopefully this saying will prove true, and America's enthusiasm for the martial arts can lead to a rejuvenation of the traditional arts in China, and across the world.

| Discuss this article online | |

| March/April 2009 Wudang Special |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2009 .

About

By Zhou Xuan Yun (Mysterious Cloud) :

Daoist monk Zhou Xuan Yun (Mysterious Cloud), grew up in a temple on Wudang Mountain, China where he was a student and later an instructor of Kung Fu and Taiji.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article