Calligrapher, Photographer, Riot Police Trainer Master Li Yancai

By Gene Ching

"Numchuk skills, bow hunting skills, computer hacking skills? girls only want boyfriends who have great skills." Napoleon Dynamite

I've seen a lot of nunchuk demos. I've seen nunchuk masters smash apples thrown into the air. Once I saw someone spin light-up nunchuks under a black light surrounded by writhing naked women in day-glow bodypaint. I've even seen a chimpanzee demonstrate nunchuks. But nothing so far has matched the nunchuk skills of Master Li Yancai.

I've seen a lot of nunchuk demos. I've seen nunchuk masters smash apples thrown into the air. Once I saw someone spin light-up nunchuks under a black light surrounded by writhing naked women in day-glow bodypaint. I've even seen a chimpanzee demonstrate nunchuks. But nothing so far has matched the nunchuk skills of Master Li Yancai.

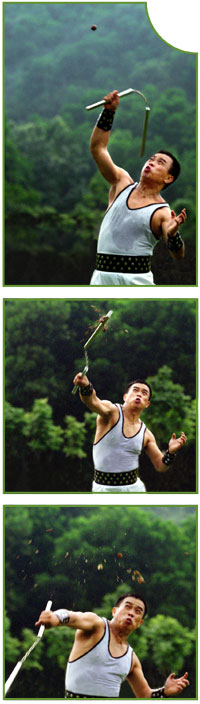

Like all nunchuk masters, Li's moves were blindingly fast. He had a few patterns and transitions that I hadn't seen before, but what caught my attention were his applications. He took apart a disposable lighter in midair. The amazing part was he did it piece by piece. First, he just chipped off the end of the fuel reservoir. Then he knocked off the striker. Finally, he smashed what remained. Three tosses, three strikes, three highly accurate results. It seemed like a trick at first, but I've seen him do this repeatedly with other people providing the lighters. If Li is that accurate with a lighter, imagine what he could do to your knuckles.

The Little Dragon's Shadow

Born in Guangdong, Li was raised by his mother, since his father worked as a wood sculptor in Hong Kong. He was a rebellious youth, difficult for one parent to handle. Being physically small, Li often found himself the brunt of bullies. He felt he needed to be stronger to take care of himself and his family and friends, so he started his training in Wing Chun. No one in his family had practiced martial arts before. Li just got the idea, saved his money and found a teacher, all by himself.

When his dad came from Hong Kong for a visit, he would bring gifts from the city. When Li was twelve, his dad brought a poster that would change his life. "They called him Li Sanjiao (Three-legged Li)," recounts Li in Mandarin. We know him here as Bruce Lee. Just like millions of people around the world, Li discovered a hero in the "Little Dragon." "As soon as I saw the poster, I went crazy. That was during the revolution, so I couldn't see his movies. But my dad brought me posters and books. I followed the drawings."

Today, over three decades after Bruce Lee's passing, he still inspires the world with his whipping nunchuks and wailing battle cries. "The impact of Bruce Lee is hard to overpass," reflects Li with admiration. "There may have been better masters, but no one beats his impact. Bruce Lee IS Chinese martial arts. Ever since I was twelve, my respect of Lee has only increased." With Lee as his role model, Li practiced even harder, absorbing Lee's philosophy of Jeet Kune Do. And yet, Li doesn't view himself as a JKD exponent. "New systems aren't bad, but it must be based in tradition and history. You cannot create something without a base or foundation. No one will understand. That won't work. Like calligraphy, you must study the masters first." This attitude makes Li far more than just another "little dragon" fanatic. "Anything good that I'm supposed to learn, I will learn. Bruce is always my idol. He gave me a lot of inspiration. Even though I practice nunchuk, I don't want to be just like Bruce. I want to improve more."

As a youth, Li participated in many youth competitions and earned first level standing (communism discouraged competition back then, so "first place" awards were replaced by levels). By age eighteen, Li had grown into a talented martial artist, recognized for his skill at free sparring and nunchuk. Being bullied as a child forged a keen devotion to serving justice, encouraging Li to pursue a career in law enforcement.

A Kung Fu Riot Cop

In 1978, Master Li enlisted in the military and was stationed in Beijing. With his skills instantly recognized, he was asked to coach a special anti-riot police squad. He spent six years there, teaching the police nunchuk skills. "The Chinese police don't always have easy access to guns," notes Li. "You can hide a nunchuk easily. When you draw it, it's not shiny like a gun or knife. It's a good weapon because it's so fast." Another of Li's startling demonstrations is to be able to draw and strike with his nunchuk before an officer can draw and shoot his firearm - it's a big crowd pleaser among police officers. "It's a great skill for close quarters?for two steps away," confides Li. "But any farther and you kill me twenty-five times already."

Li's nunchuk program proved its merit on the mean streets of Shenzhen. One of his students, Officer Guo, was the team leader of the local police squad. He had studied nunchuk under Li for only two years. The squad was trying to apprehend a murderer who had killed twenty-three people and then snuck into Shenzhen. What was worse, the murderer was a kung fu coach - physically large by Chinese standards and a former sparring champion. The police had him trapped in a bank where he had tried to get some cash, but with hostages involved, they couldn't take him out with a bullet. Officer Guo boldly walked in and called the man's name. The man reached for his gun, but Officer Guo caught him with his nunchuks first. When word got out of Guo's success, Li's nunchuk program became very popular.

Since then, Li has been on the cover of the major mainland martial arts magazines. He has an entry in the Chinese encyclopedia of masters and was featured in a high-profile 2004 documentary series, The Secret of Chinese Gongfu, which focused on forty of the China's most outstanding masters. Such publicity in the martial arts world of mainland China brings certain responsibilities. "People bring the magazines to challenge me," confessed Li. "Most of them become respectful after they see what I can do. They ask me to teach them or become my friends. Some try to fight me. I try not to hurt anyone very badly." The Chinese magazines suggested that Li launch a website forum to deal with the overwhelming responses, but even that got out of hand. Now he doesn't bother with it anymore. Sometimes his students still reply, but Li doesn't hold much regard for forum challenges. "Kung fu is about action, not talk."

The Martial Tao of Bugs

Beyond coaching the anti-riot squad, Li used his time in the military to study his other passion - fine art. His father, being an artist, encouraged Li with gifts of paintings, posters and art books, on top of the martial arts resources. He began training in classical calligraphy at a very young age and was already entering art competitions at age seven. By the time he reached maturity, he had already received many calligraphy awards. Li took advantage of his time in Beijing to study under some of the great masters residing there, taking private lessons in art and calligraphy. His skills earned him the position of art director for the military newspaper.

Li also became an award-winning photographer, specializing in shooting bugs. Why bugs? "It's the Tao of bugs. In Chinese martial arts, you must go from movement like a wild horse to stillness like a quiet pond. Bugs are genius at this. They are all about survival. I connect to them spiritually. The Tao of bugs and the Tao of martial arts are the same. The most important approach is how you insist on your life. Some bugs only live for a few days, but in those short lives, they fully express themselves. They use every moment of their life. By watching this, I come back and do whatever I do very persistently. I do the best I can and I don't waste any time. When I start painting calligraphy or practicing kung fu or photographing bugs, I just get into it. There's no sense of time. I just do it for hours. When you look at bugs, if you don't look at them from their angle, you cannot possibly relate. But if you can see like them, it will come to you."

Li parlayed his artistic talents into a career in interior design and remodeling. Today, he oversees the Shenzhen Great Wall Decorating & Construction Co., Ltd. which fuses practical and aesthetic design in living and work spaces. In an expression of his adoration, he designed a custom-made ?nunchuk' staircase banister in his office. Li attributes all of his achievements in nunchuks, calligraphy, photography and interior design to Bruce Lee's spirit. "I'm grateful to my parents for my life, but Bruce gave me the inspiration."

Are Nunchuks Chinese or Japanese?

Are Nunchuks Chinese or Japanese?

Bruce Lee and his nunchuks form the most popular martial image in the world. Despite Lee's Chinese roots, nunchuks are commonly attributed to Okinawa (although some claim that no traditional Okinawan nunchuk forms exist). Nunchuk, or more properly Nunchaku, is a Japanese word. Nun means "identical." Chaku means "section." With the worldwide proliferation of nunchaku, many derivations of this word have arisen in the common vernacular, such as numchuks, chakus and chuks. In Mandarin, a different term is used - erjie gun (two section staff chinese). Some claim that the erjie gun goes back to the fall of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) in China. An erjie gun creation legend attributes it to the first Song Emperor, a venerated warrior who reigned from 906 to 976 CE. The story goes that he broke his favorite staff on the battlefield and lashed it back together again, combining soft and hard, thus creating the first nunchuk. That weapon was actually a two-handed pole arm, but after the war subsided, Chinese nunchuk advocates claim that the weapon shortened into its present form for more casual use. Some early examples of Chinese nunchuk-like weapons do exist, but the debate remains unresolved.

Despite Li's loyalty to Chinese kung fu, he doesn't particularly espouse an opinion on the origins of nunchuks. "Who cares what country it comes from? Bronze covered with gold is still bronze. Only solid gold is solid gold. If someone in China can win the championship in Tae Kwon Do, that's great. If an American can do the best nunchuk, then he's the ?king of nunchuks.'" A staunch advocate of Chinese culture, Li's not attached to nationalistic propaganda. "We say we have five thousand years of history. But if the Chinese can't do Chinese martial arts well, it's still no good. Even if you inherit all the history, you cannot forget to improve upon it and develop it for modern times. You must go the next step. Otherwise, if you just stay like that, it's useless. It's history. It's not you."

Here in America, police use a different Okinawan weapon, the tonfa, instead of nunchuks. Nunchuks are banned in many states. How does Li feel about that? "It's good that nunchuks are illegal in America. They're also banned in Hong Kong, Thailand and Japan, but you can carry them in China. China has to catch up. The nunchuk is much faster than the knife. I can use a nunchuk against ten people wielding knives, no problem. It's easy to carry and it can be a very deadly weapon."

In 2003, Li's nunchuk skills were showcased at a celebration for his idol, the 30th anniversary celebration of Bruce Lee in Hong Kong. Li performed at an honorary ceremony at Lee's old neighborhood, gave demonstrations for the celebration and for Hong Kong TVB, and even did a special program that was played exclusively on 2400 double-decker Hong Kong Buses. Regardless of origin claims, Li notes that throngs of Japanese fans attended the celebration. "They idolize Lee as much as the Chinese people. The Japanese wore these formal suits all throughout - sweating in Hong Kong's tropical heat - all out of respect." Just like his hero, Li sees no barriers in the martial arts as to race, nationality, color or creed. "Very simply, martial arts originated in China, but belong to the world."

The Tao of Nunchuk Skills

With such a diverse portfolio, Master Li Yancai sees no limitation to the expression of martial arts in today's modern world. "Many martial artists are narrow-minded. They always think they are #1. That's wrong. That will limit your development. It's very simple; if you think you're better, just go to the leitai (sparring ring) and fight it and see who wins and who loses. However, some people don't do that. They just say they're the best. That's not going to work. All martial arts have good and bad. You just can't have one to represent them all. There is no ?best.'

"But Chinese martial arts cannot say it's all about fighting to win. There's a wide range of disciplines like taiji, qigong, and forms for performance. Every single system has value or it wouldn't exist. Bad systems die off. It's really about whether you practice it well or if your skills are good. If you have no skills, it's not the system.

"If you persist, and you try to follow the truth to your maximum capacity, you will achieve the height of your talent. No system is that much better than another. If you see someone that has something better that you don't have, absorb it. Then you can get more. Combine everything together. Just like calligraphy and photography, like anything, there's no limit. There's the mountain, then there's a higher mountain. I still keep improving. Compared to the highest levels, I still feel like a kindergartner.

"You have to have absolute truth in martial arts. Kung fu comes from your blood and sweat. It's an exchange of time and effort, plus understanding. You need an open mind. You absorb everything. Different skills are all good. Wulin yi jia (martial arts one family). I don't really learn from a lot of systems, but if they have some better skills, I will learn them. Like Bruce Lee."

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2005 .

About

Gene Ching :

For more on Master Li Yancai, visit his website at www.liyancai.com.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article