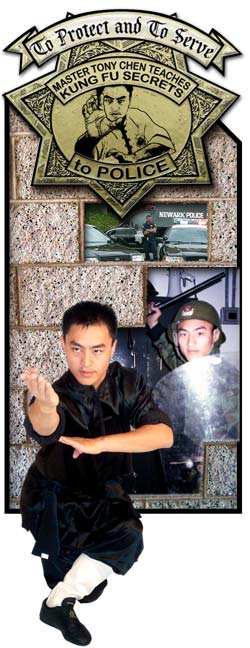

Master Tony Chen Teaches Kung Fu Secrets to Police

By Gene Ching

Walk into any of the U.S.A O-Mei Kung Fu Academies of California and you?ll hear the kids shouting the school rules after every class: ?Listen to your teachers! Listen to your parents! Always do your best! Never say ?can?t?! Use kung fu only for good!? It?s that last one that echoes out, burrowing into the school?s nooks and crannies, seeping into the hearts of the youth. Nowadays, popular martial arts are so dominated by extreme blood sports, gory movies and violent videogames that it?s not surprising how many overlook this fundamental law. ?Reality-based street fighting? is the order of the day, with more martial arts schools preaching no-nonsense ?effective? combat. But does no-nonsense imply no ethics? Embedded deep within traditional mores is a most important lesson - an unspoken moral code. Never discard an ancient constraint if it perpetuates morality. Should the arts produce good-hearted warriors or killing-machine street thugs? Any school that trains criminals is adding to the problem. ?Only for good? is unquestionably the most important rule of all martial arts. With a firm grasp on this principle, your journey down the warrior?s path will always be true.

Walk into any of the U.S.A O-Mei Kung Fu Academies of California and you?ll hear the kids shouting the school rules after every class: ?Listen to your teachers! Listen to your parents! Always do your best! Never say ?can?t?! Use kung fu only for good!? It?s that last one that echoes out, burrowing into the school?s nooks and crannies, seeping into the hearts of the youth. Nowadays, popular martial arts are so dominated by extreme blood sports, gory movies and violent videogames that it?s not surprising how many overlook this fundamental law. ?Reality-based street fighting? is the order of the day, with more martial arts schools preaching no-nonsense ?effective? combat. But does no-nonsense imply no ethics? Embedded deep within traditional mores is a most important lesson - an unspoken moral code. Never discard an ancient constraint if it perpetuates morality. Should the arts produce good-hearted warriors or killing-machine street thugs? Any school that trains criminals is adding to the problem. ?Only for good? is unquestionably the most important rule of all martial arts. With a firm grasp on this principle, your journey down the warrior?s path will always be true.

Master Tony Chen, founder of the USA O-Mei Academies, places the "only for good" rule last for emphasis. He stresses using kung fu for good through his personal community service, particularly in his work as a police combat instructor. Chen taught kung fu as a full-time police combat instructor in China; He continues teaching police defensive tactic seminars in America today. Chen freely reveals to peace officers some closely-guarded secrets of his venerated lineage - tactics typically reserved only for "indoor" disciples - to diversify their skills so they can better accomplish their duties. To Chen, part of his duty as a master is to be a police combat instructor.

The Best Art for a Street Beat

Teaching cops is not something just any martial arts master can do. First of all, the master must be experienced in real-world combat. Many of today?s masters have never actually fought for real; while they may be qualified as civilian instructors, they would be acting with gross negligence if they passed themselves off as police combat instructors. But teaching police is far more complicated than simply having survived a few bar fights, or even a no-holds-barred match.

American peace officers are bound by strict use-of-force protocols which render many ?reality-based street fighting? techniques unusable. Often, those street tactics rely heavily on ground fighting, a residue from ?reality-based? no-holds-barred contests like UFC or K-1. However, it?s not practical for an armed police officer to go to the ground; There, it would be too easy for a suspect to get at an officer?s weapon. What?s more, a cop choking out a suspect looks bad in the eyes of the American public. Restraining a combative suspect requires the utmost tact and delicacy, never mind that the suspect is probably violent, big and looking to hurt you. The police response must not injure the individual unnecessarily. In light of brutality accusations in cases like Rodney King - or, more recently, Nathaniel Jones -- use of force is a very sensitive issue.

This is where police defensive tactics are distinct from military combat. For the police, restraining methods outweigh lethal ones; for the military, it?s the opposite. Additionally, the military places less emphasis on hand-to-hand combat since soldiers are better armed (cops don?t have tanks, jets, missiles or battleships). The objective of war is to destroy the enemy, while the objective of the police is to protect the innocent. These different intents completely change the techniques employed.

What?s more, both the police and the military have needs that differ pedagogically from those of a civilian in a martial arts school. Civilian students have more time, and for the most part are training for health. No doubt everyone who pursues the martial arts is looking to learn some self-defense, but for civilians it?s a pastime, not a profession. Law-abiding citizens avoid confrontation - we don?t look for fights. Physical conflicts are left to peace officers and the armed forces to resolve.

Police aren?t looking for the ?art? of martial arts. They prefer easy and effective techniques to those that are complex and sophisticated. Combat methods must be simple to learn and simple to use, without requiring a lot of practice. Police don?t have time for long hours of horse-stance training. But they do want to be better prepared for their job. And that job grows more difficult each day because criminals are studying the martial arts too. In fact, due to advances in modern media, martial arts are more accessible than ever. While incarcerated together, prisoners commonly and covertly train counterattacks to standard restraint methods. So today, to counter the counters, some police are digging deeper into the ancient mysteries of kung fu.

From National Combat Champ to Police Instructor

Master Chen?s father, Chen Jian, is a famous master of traditional O-mei kung fu. O-mei (or Emei) is a sacred mountain in Sichuan Province, renowned throughout China for its natural beauty and its Buddhist and Taoist temples. It also has a long and respected martial legacy. Chen senior taught special police forces in Sichuan for four years. In March 1985, he led their team to a gold medal at the First People?s Republic of China National Armed Forces Tournament and Exhibition. Twenty-eight military and police teams representing both provincial and large municipal precincts gathered in Nanlin City, Guanxi Province to spend a week duking it out. The officers competed both in Sanshou (free sparring) and Wushu Taolu (forms). The Sichuan team emerged victorious in Sanshou with Chen Jian as coach.

Given his father?s reputation, one would have expected Tony Chen to follow in his footsteps; instead, he took an entirely different route. In 1991, Master Tony Chen won China?s national champion title in Sanshou in the 52 kg division, one of four such national titles that he would capture during his competitive career with the Chengdu Sports University in Sichuan. Winning the title earned him a starring role in an action movie about the SWAT team of Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province (a.k.a. Canton) titled Tejing Xiang Feng (add Chinese). It was a small film. In fact, Master Chen searched for a copy in China for years but didn?t find one until he came to America and looked in a Chinatown VCD store. Chen choreographed the fight scenes in that movie and worked closely with the film?s technical advisor, officer Zeng Ye (add Chinese). Zeng had a bit part too, as the SWAT instructor, emulating his real life position. Impressed with Chen?s fighting prowess, Zeng offered Chen a position teaching at the Police Academy in Shenzhen after the production wrapped. Chen was only 19 at the time. Chen and Zeng formed a lifelong friendship, and Zeng was later promoted to police chief in Guangdong.

Shenzhen City, Guangdong, was a unique experiment in China. Officially labeled as a Special Economic Zone (SEZ), Shenzhen was essentially a ?capitalist? city under Communist rule. Situated on the edge of Guangdong with a commanding access to Hong Kong, it became a boom town. In the ?80?s to ?90?s, China?s 10% economic growth rate was one of the highest in the world. Guangdong province was growing at a rate of 18%. But when Master Chen came to Shenzhen, the SEZ had a cancerous growth rate of 45%. Big money brings big crime, and corruption was rampant. As Shenzhen scrambled to outfit its police department to meet the growing demands of its mounting population, the Department made an aggressive search for new cadets. In that region, not only did people speak Cantonese instead of the nationally-mandated language of Mandarin, there were many smaller regional dialects like Saiyup, Samyup, Hakka and more. This required a diverse police force with officers who could communicate in all the different languages and cultures. It was up to Chen to teach that new wave of police cadets how to defend themselves. Additionally, many senior officers needed ongoing course work to qualify for openings and promotions, so Chen found himself teaching a wide range of students, from rank beginners to seasoned veterans of the force.

In the Academy?s program, recruits and officers studied self-defense in a two-hour class, five days a week. The classes averaged around 40 students per class, with both men and women. Of course, the officers in ongoing training had previous combat experience. But many of the recruits were new to the martial arts. Master Chen followed a basic curriculum to meet all of their needs.

The syllabuses concentrated on Sanshou techniques, boxing and wrestling, mostly basic punch, kick and joint-lock methods. There was no emphasis on any particular style, just efficient loose techniques. The police did learn a form called Qindiquan (add Chinese) or ?grappling enemy fist,? but it was short and fundamental, used primarily for exercise. Physical conditioning also fell under Chen?s command. In a very short time he produced capable fighters, ready to face the mean streets of Shenzhen.

Cops Without Guns

With lingering cold war images and memories of Tiananmen, many westerners envision Chinese police to be cold-blooded and brutal. Truly, some Chinese police techniques would elicit an outcry of brutality if caught on a U.S. videocam. But just as each state in our union has different protocols, China?s use of force is based on its needs and resources. Here in America, an officer may be equipped with the latest computer technology like a laptop that ports right into the squad car and can survive a three-foot drop. But in China, many cops don?t even carry a gun. Typically, many low-ranking Chinese cops are equipped with a badge and minimal hardware - perhaps some cuffs, restraint ties, a baton, a radio and maybe a tazer (an electrical shock stunning device.) Often, they must capture armed suspects by empty hand.

To compensate for less gear, their tactics are more extreme, so traditional kung fu is a treasured resource. For example, Chinese police are well versed in restraint-tie techniques. The restraint tie, really little more than a simple length of cord, is one of the most common tools for a Chinese cop, also one of the oldest and most traditional. It has been used for dynasties, so a vast arsenal of techniques exist. Beyond the basic procedures for quickly ?hog-tying? a suspect, there are methods for neutralizing knife or baton attacks. In the right hands, a rope is all that?s needed to subdue an armed assailant. Because China has the world's largest population, crowd management is another potent concern. Mounted police are almost unheard of there, so Chinese cops are trained more with riot shields and batons. For Chen this was easy, since the time-honored ways of traditional sword and shield hold true. The only necessary adaptation was to eliminate the ground-rolling prevalent in sword and shield.

Another problem with Chinese law enforcement is that more people practice the martial arts. Since cops go hand-to-hand more often, this is a very serious issue. There have been recent efforts to control the teaching of kung fu to the public. Chen remembers when some forms of kung fu were banned in certain areas. Styles like Wing Chun were targeted, since close-combat methods present the most trouble for an arresting officer. However, China has tried to ban martial arts since imperial times with little success. Kung fu always prevails. Unfortunately, it?s as much a weapon for criminals as a tool for police, so Chinese cops must always be prepared.

American Law Enforcement and the Martial Arts

When Master Chen opened schools in America, his combat experience and emphasis naturally attracted numerous public servants who required fighting skills as part of their day-to-day job. Active police officers, consulate security, prison guards and military students began attending his classes, and in due course he was asked to teach some special classes for their respective departments. He soon found himself giving lessons to the police again, but in a totally different context.

In America, police officers get a fair amount of defense training at the Police Academy, which can vary according to the standards set by different states. Generally, cadets learn basic control and take-down techniques, nothing fancy, with successive training varying upon on the Department. Most training is done on days off (overtime) or by sending Officers to schools that meet State requirements. For example, California has an office called Peace Officers Standardized Training (POST), which mandates training requirements for all types of Academy peace officers through bi-yearly courses. These courses can include driving, investigation, firearms, etc., including "defensive tactics." All Departments have designated "defensive tactics" instructors who have attended the State-approved POST course. Part of their job is to take what techniques they learn back to their Department and teach other officers. Other officers may pay for classes on their own, or take martial arts or boxing.

Today, martial arts are beginning to play a larger role in U.S. law enforcement. Liability issues arise each time an officer draws his or her weapon (not to mention reams of paperwork for everyone involved), making hand-to-hand methods preferable to weapons use. Judo and Jujitsu have been popular styles for hand-to-hand, largely due to their array of joint locks and restraining holds. But the Chinese arts have a wealth of these methods too, what the Chinese call qinna (a.k.a. chin na add Chinese) - the way of joint locks and pressure points. Surprisingly, internal styles like Tai Chi, Bagua, Xingyi and Baji are proving to be the most useful. While many of today?s practitioners recite these styles just for the health and meditative benefits, they are jam-packed with hidden combat applications that make for practical restraint techniques.

Catch Me If You Can

Master Chen?s first police combat seminars were experimental. Although he had taught police before, that was in China. He had no idea what the level of combat proficiency for American police was. So Chen went with an old school kung fu strategy. He let the cops test him.

Chen asked the cops to try and catch him using their standard techniques. Now, most American police officers are big -- bigger than average Americans and much bigger than most Chinese cops. They are often well-trained in judo, jujitsu and boxing. Chen, who fought at 52 kg (less than 120 lb) as a youth, is not that large. However, using his kung fu skill, he could still find gaps. He could still escape. That immediately caught the attention of the police. They listened enthusiastically as Chen revealed how to seal those gaps so no one could ever escape, no matter how big. ?American police have skills already,? states Chen with a smile, ?so I focus on stuff they?ve never seen - straight from China.?

Continuing to improvise, Chen inquired about typical situations the officers faced on the streets. A common scenario was dealing with a prone suspect who had sandwiched his hands between his body and the ground to resist being handcuffed. A Chinese cop might counter with a percussive response, but the strict levels for the escalation of force left American police in a quandary. Chen revealed a simple pressure-point technique that gave the officers immediate access to the suspect?s wrists. The police were delighted and invited him back to learn more.

According to Chen, ?Cops have no time to practice routines, nothing complicated. They only have one goal - not in the ring, on the street. They have to be really gentle, really simple, stuff they don?t need to practice.? On the whole, Chen felt that American police were easier to teach. For the most part, American officers are physically bigger and stronger than the cadets he trained in China. They also had more martial arts experience from prior training in general. But what had the most affect on Chen?s American police combat curriculum in contrast was liability. The limitations of liability left considerably less material to teach.

The Code of Silence

In the martial arts, secret techniques still exist. Such secrets are only revealed to the most intimate students, the ?indoor? disciples who will carry on the lineage. It?s often contested. Rival lineage factions often argue about which master received secret transmissions from the grandmaster. Some westerners even reject the very notion that a master would keep secrets from a student. But the truth of the matter is that the martial arts are a weapon, and no weapon can be handed out indiscriminately. It can only be passed down to students with good hearts. Otherwise, don?t pass it down.

?We keep these techniques secret so the cops keep something,? says Master Chen. He elaborates, ?I teach them more natural stuff. I also teach some secret stuff not for the public - indoor techniques.? By their community service, peace officers earn the right to access these techniques, just like the right to bear arms. If you want to learn all the secrets, look into your own heart. Use kung fu only for good.

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2004 .

About

Gene Ching :

Master Tony Chen oversees four U.S.A. O-Mei Kung Fu Academies in California in the cities of Oakland, San Leandro, Sacramento and Fremont. Click www.usaomei.com or contact his Oakland school at 510-465-1925 for more information.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article