By Gene Ching

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

What most people believe about Shaolin today is fake, made up by the media. There is an intimate connection between Shaolin and fiction, especially from television and the movies. These mediums have not only had a profound influence on public perception, they actually had a hand in the evolution of Shaolin Temple itself over the last half century. For most Americans, it began 47 years ago, when we heard the word "Shaolin" on TV.

What most people believe about Shaolin today is fake, made up by the media. There is an intimate connection between Shaolin and fiction, especially from television and the movies. These mediums have not only had a profound influence on public perception, they actually had a hand in the evolution of Shaolin Temple itself over the last half century. For most Americans, it began 47 years ago, when we heard the word "Shaolin" on TV.

In 1972, the TV show Kung Fu brought David Carradine’s whitewashed Shaolin monk Kwai Chang Caine into U.S. households. Apart from Mr. Sulu on Star Trek, Kung Fu was the first American TV show to have Asians in major supporting roles. Caine’s role as an itinerant Shaolin monk in the Wild West inadvertently became the metaphor for Asian Americans in television for decades to follow. Meanwhile, at the movies in the following year, Bruce Lee also brought Shaolin Temple into American awareness with Enter the Dragon. The opening fight scene between him and Sammo Hung was allegedly set at Shaolin, although the monk witnesses were completely overshadowed once Bruce whipped out his nunchuks. Nunchuks and Kung Fu cat calls are still all that pop culture can seem to remember about Bruce.

Half a decade later, another pivotal Shaolin Temple movie premiered – The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978). Also known as Master Killer, this film is a certified Kung Fu classic and the ultimate example of the "obtuse Kung Fu training methods for revenge" story arc that is so pervasive in the genre. For many fans, The 36th Chamber of Shaolin defined Shaolin Temple. While it isn’t as well known as Carradine or Lee, it was the inspiration for the Wu-Tang Clan’s premiere album, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) in 1993, a pivotal work that reshaped Hip Hop.

Remarkably, none of these films showcased genuine Shaolin Kung Fu. When David Carradine took the role of Caine, he was a dancer, not a martial artist, and even under the direction of Masters Kam Yuen and David Chow, his lack of martial skill still shows. And although Bruce Lee demonstrated a signature Northern Shaolin triple kick in Enter the Dragon, he had already developed his own style, Jeet Kune Do, by then. Tragically, Lee died before Enter the Dragon was released.

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin was pure Hung Gar (洪家). While Hung Gar is a form of Southern Shaolin Kung Fu, it is not what is practiced at Shaolin Temple today. Nevertheless, Hung Gar was the most influential cinematic style for over four decades – during the late '70s and early '80s, the Golden Age of Kung Fu movies, as well as for the earliest Kung Fu film franchise of the '50s and '60s. The 36th Chamber of Shaolin features two titans of that Golden Age, Director Lau Kar-Leung (1936–2013 刘家良) and leading man Gordon Liu (刘家辉). They were Kung Fu brothers in real life, both students of Lau’s father, Hung Gar Master Lau Charn (?–1963 劉湛). Lau Charn was a direct student of Lam Tsai Wing (1861–1942 林世榮) as well as a director and actor himself. He worked on several of the original black-and-white Wong Fei Hung movies, even playing the role of Lam Tsai Wing in some of those films. This Wong Fei Hung film franchise was based on the real-life folk hero and Hung Gar master Wong Fei Hung (1847–1925 黃飛鴻), Lam’s master. The franchise starred Kwan Tak Hing (1905–1996 關德興) who was another Hung Gar student of Lau Charn. The franchise went from 1949 to 1970, spanning some 68 films (25 films were released in 1956 alone) and still holds the Guinness Book of World Record for the "Most Films in a Film Series." No style holds as much sway over the first four decades of Kung Fu movies as Hung Gar.

Traditional Shaolin and Modern Wushu

Not only did those early films fail to represent genuine Shaolin Temple Kung Fu, none of those films were shot on location at Shaolin Temple. When one finally was, everything changed. Kung Fu was filmed in Hollywood and the other two films were shot in Hong Kong while it was still under British control. Mainland China was just opening up. In 1972, the same year that Kung Fu premiered, Nixon became the first American president to visit the People's Republic of China, ending a quarter century of silence between the U.S. and the P.R.C. At that time, most of China didn't even know that Shaolin Temple had survived the Cultural Revolution of the previous decade. In a historic twist of international diplomacy, Nixon unwittingly played a role in the spread of Chinese martial arts. Some of the very first Chinese ambassadors to the White House were Wushu masters, the first generation of this modern sport style, including a then 11-year-old Jet Li.

By auspicious coincidence, Jet Li had a key role in reintroducing Shaolin Temple to China. In 1982, the movie The Shaolin Temple was released, Jet’s debut film and the first to use the original Shaolin Temple of China on Songshan as the location. However, once again, the film didn't showcase Shaolin Kung Fu. Instead, the cast was comprised of several of the nation's leading Modern Wushu champions like Yu Hai (JAN+FEB 2007 cover master 于海), Yu Chenghui (JUL+AUG 2012 cover master 1939–2015 于承惠), Ji Chunhua (SEP+OCT 2015 cover master 1961–2018 计春华) and Hu Jianqiang (OCT 1999 cover master 胡堅強). At that time, Shaolin Temple had been partially restored. The last century took its toll on Shaolin. Prior to the Cultural Revolution, there was a Japanese occupation and the warlord period as the Republic of China gave way to the communists. Shaolin Temple had been mostly forgotten and abandoned, save for a few stalwart monks and local folk masters. The Shaolin Temple was a blockbuster and droves of children descended on the holy shrine from all across China in hopes of learning Shaolin's glorious legacy. Local tourism boomed, giving Shaolin much-needed income for further restoration. Shaolin became the world's largest martial arts community, as well as one of the most illustrious temples in China.

But what actually remained of Shaolin Kung Fu? It wasn't Hung Gar despite its Southern Shaolin roots. It wasn't Jeet Kune Do. It certainly wasn't whatever David Carradine was doing back in the seventies. Modern Wushu was introduced to the region both by the government and left in the wake of those Jet Li movies. Nevertheless, a curriculum of traditional Shaolin Kung Fu remained, preserved by the local villagers and those few surviving monks. As Shaolin was restored, so were its treasures – its martial legacy, its medicine, and, of course, its Chan Buddhism. Shaolin Temple Kung Fu, or Songshan Shaolin Kung Fu (named after the Song mountain range where Shaolin Temple is located) is a distinct style. And with thousands of masters graduating from the region every year, Songshan Shaolin is growing faster than any other style of Kung Fu today. The essential forms of Songshan Shaolin Kung Fu include Xiaohongquan (小洪拳), Dahongquan (大洪拳), Liuhequan (六合拳), Changhuxinyimen (长护心意门), Qixingquan (七星拳), Meihuaquan (梅花拳), Lohanquan (羅漢拳), Taizu Changquan (太祖长拳), Paochui (炮捶), Xinyiba (心意把), Tongzigong (童子功), and many others. A warrior monk won’t know every single form propounded at Shaolin (there are literally hundreds of forms practiced there now); the traditionalists are all familiar with this central core curriculum.

Shaolin in America

The first actual Shaolin monk to set foot in America was Venerable Hai Deng (1902–1989 海灯). Ironically, this was also in the wake of Jet Li’s The Shaolin Temple film. The film's popularity inspired CCTV to make a documentary on Hai Deng, who was one of the most advanced practitioners at Shaolin Temple at the time. He was renowned for his yizichan (one finger chan 一指禪), a seldom replicated qigong skill where he could do a handstand supported only by one finger. Riding the coattails of The Shaolin Temple, the documentary was later re-edited to include Jet Li and distributed under the title Abbot Hai Deng of Shaolin (少林海燈大師), even though Hai Deng was never an abbot at Shaolin. The documentary brought Hai Deng fame and allowed him to come to America in 1985. He visited another pioneering monk, Venerable Hsuan Hua (1918–1995 宣化), in San Francisco. Hai Deng did teach some Shaolin Kung Fu then, primarily to Hsuan Hua’s Buddhist pupils, but outside his circle few ever even knew about Hai Deng’s visit.

America’s first exposure to Shaolin Kung Fu came much earlier through the Shaolin diaspora. While China was closed, Hong Kong was still under British rule until 1997 so most Chinese emigrated from southern China, bringing with them those southern Shaolin styles, most notably Hung Gar. In 1963, Grandmaster John Leong (Jan+Feb 2008 cover master 梁崇) brought Hung Gar to the United States from his native Southern China. And for Americans of that generation, Hung Gar was Shaolin Kung Fu. He opened his school in Seattle, the Seattle Kung Fu Club, coincidentally at the same time Bruce Lee was teaching there. That was long before America had heard of Kung Fu. The Seattle Kung Fu Club is still thriving, and Grandmaster Leong continues to teach there even after celebrating his 80th birthday in 2017.

Nearly three decades after he came to America, Grandmaster Leong established ties with Shaolin Temple by becoming an honorary advisor for the Temple in 1990. And in 1992, he was instrumental in bringing the very first troupe of Shaolin monks to the U.S. for a Kung Fu demonstration tour. The troupe included Grandmaster Liang Yiquan (梁以全), founder of one of the top three Kung Fu schools near Shaolin, the Shaolin Epo Martial Arts Zhuanxiuyuan (少林鹅坡武术专修院), as well as Shi Guolin (释果林) and Shi Yanming (釋延明), the first two Shaolin monks to permanently reside in the U.S. Guolin and Yanming led the pack, and today there are countless Shaolin monks, disciples and masters living and teaching in America. There’s even one teaching with Grandmaster Leong, Master Gao Xiong (高祥).

A Child Selected for Shaolin Temple

Nearly a quarter century after Grandmaster Leong began teaching Hung Gar to Americans and two years after Hai Deng first came to U.S., Master Gao Xiong was born. Like many of his generation, he was inspired by Kung Fu movies and TV. He liked to watch people flying and walking on walls. Some of his relatives on his grandmother’s side lived near Shaolin, so at the tender age of nine, he went. He was enrolled in the Henan Daxue Wushu Xueyuan (Henan University Martial Arts College 河南大学武术学院), first starting there in nearby Kaifeng. The college provided an elementary through university education that combined academic studies and Shaolin Kung Fu, all under the auspices of the local Dengfeng government and tourist board.

After the first year, he was selected to train at Shaolin Temple. “There were 400 or 500 Shaolin students at that school,” recalls Gao in Mandarin. “Shaolin selected 10 of us kids. We were tested on basics – basic routines, jumping, squatting. They were looking for those born with talent.” Naturally Gao was excited to be selected, but it was challenging. “I was so tired,” confesses Gao. “It was too hard. Sometimes the master hit me hard.” Both the school and the temple were very harsh. Gao was disappointed. It wasn’t like TV or the movies. There was no flying or walking on walls. However, Gao stuck it out because it had always been his decision to go, plus he loved martial arts. “Many classmates gave up.”

Training at Shaolin Temple was different from what he experienced at the college. The schedule was similar – waking at dawn, training, short meal breaks, more training, and so on. Shaolin classes were smaller so there were less places to hide. And the curriculum was more rooted in traditional Shaolin Kung Fu instead of Modern Wushu. In addition, more time was spent in sitting meditation – in Chan. Gao wound up staying for nearly a decade and a half. “Most Shaolin novices move on after a decade,” says Gao.

When Gao hit his teens, he started performing for visiting dignitaries. By 2002, he began travelling abroad to perform. It was a privilege. Few teenagers were able to leave the country back then. He was sent to French Polynesia to demonstrate with a Shaolin troupe, but it wasn’t a formal stage production, just Kung Fu. Later, Gao participated in a show in Canada and then performed with the Chinese State Circus for 2 years when it toured the United Kingdom. That circus retained a squad of five warrior monks. The tours ran for about ten months and he went on two tours. Gao looks back on his performance years somewhat wistfully by quoting an old Chinese saying “One minute on stage, ten years of work (tai shang yi fenzhong, tai xia shi nian gong 台上一分鐘, 台下十年功)."

Hung Gar in Singapore

Grandmaster Leong’s son, Robin Leong (Nov+Dec 2017 cover master 梁俠兒), immigrated to Singapore around the turn of the millennium, pursuing his burgeoning film and acting career. A staunch Hung Gar proponent, he found himself at Shaolin Temple for a TV role, cast as an American martial arts champion in the Singaporean TV show The Challenge (谁与争锋) which was shot on location. He trained some Shaolin Temple Kung Fu there; it was the only time he digressed from training Hung Gar.

When the show was televised, Robin was besieged with requests to teach Kung Fu, so he founded his own school – Ch’i Life Studios. He originally envisioned it to be a martial community center that offered Taekwondo, Karate, Capoeira and, of course, Hung Gar Kung Fu. He culled some Shaolin Temple masters to coach there too, and with their help the Kung Fu Kids program became very successful. Ch’i Life Studios now has thousands of students and multiple facilities in Shanghai and Singapore, all located in upscale neighborhoods, and anyone who’s seen Crazy Rich Asians knows that Singapore does upscale well.

Ch’i Life is also part of his father’s Seattle Kung Fu Club and Master Gao is now teaching Shaolin Temple Kung Fu there. What’s more, he’s studying Hung Gar, taking private lessons at least twice a week from Grandmaster John Leong. With his hardcore Shaolin foundation, Gao is picking up Hung Gar quickly. Robin is fascinated by the exchange. “Literally it was like Taming the Tiger,” reflects Robin, “the beauty of watching two styles that are so close, yet so far – uniquely paralleling the historical link we share with Shaolin.” According to Robin, Gao has been progressing steadily in Hung Gar and the prospect of another proponent of his famous style fills him with hope. “Master Gao has been such a great Hung Gar student, always open to learning new things,” says Robin. “The times we have shared training together with my father has been very special. He is my eternal little Kung Fu brother (he is only 31 years old compared to my seniorly 47 years), and sharing our knowledge and skills with each other has been very rewarding.”

Songshan Shaolin and Hung Gar Unity

Master Gao took a Shaolin name, Shi Yan Xiang (释延祥), but he goes by his birth name nowadays. He stands to inherit two of the most glorious legacies of Kung Fu. “Training Hung Gar is the same as training Shaolin,” says Gao. “Hung Gar has more low stances. It’s more square and it’s associated with 5 elements and 5 animals. Shaolin is more linear. Hung Gar changes directions more. Because it’s southern Shaolin, it has more powerful fajin (explosive energy 發勁), more constant fajin. Shaolin only emits fajin when attacking. Hung Gar trains overall power. It’s not relaxed in the same way as Shaolin. There’s more upper body use. It’s more muscular. It still derives power from the roots, but with more hand strikes.” The signature gesture of Hung Gar is the kiu sau (bridge hand 橋手). With Hung Gar’s domination on screen, it appears in other non-Hung Gar films like Big Trouble in Little China (1986). Gao sees the connection. “The kiu sau is in Shaolin Eight Section Brocade Qigong, but there it’s just a stretch. In Hung Gar, it’s a block.”

Today, traditional arts are challenged to pass their legacies down to a twitter-ADHD-attention-span generation. There are no shortcuts in Kung Fu and the tremendous dedication and discipline needed to attain deep skills takes more than many are willing to put into it nowadays, especially from childhood. However, thousands of graduates of Shaolin Kung Fu have had a solid foundation hammered into them from childhood from masters that hit "hard." Grandmaster Leong isn’t the only traditional master to take in a Shaolin graduate. And many Songshan Shaolin masters are starting to look towards the senior traditional Kung Fu grandmasters for guidance. Herein may lie the key to preserving both Songshan Shaolin and other forms of traditional Kung Fu for future generations – cultural exchange.

“All Kung Fu is the same, just style different,” says Gao. “But personally, I still prefer Shaolin.”

| Discuss this article online | |

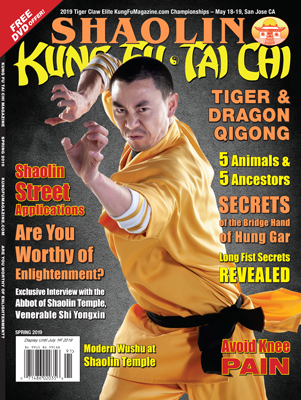

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine - Spring 2019 | |

| Shaolin Special 2019 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2019 .

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

About

Gene Ching :

For more on Grandmaster John Leong’s school, visit SeattleKungFuClub.com. For more on Master Robin Leong’s schools, visit Chi-Life.com. For more on Master Gao Xiang visit shaolinKungFuChanUSA.com.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article