By Kurtis Fujita

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

On a Sunday in San Francisco’s Chinatown, the fragrance of sandalwood incense along with the measured chants of Buddhist devotees float wistfully down from the Gold Mountain Sagely Monastery. The echoes of both rest ardently on the threshold of the the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu Studio The school, named after the renowned sifu, is as much a fixture of the Chinatown community as the man himself. In many ways, it is hard to separate the two as Grandmaster Wong has invested so much of himself into his art and students that both have a strong reputation in the world of Chinese martial arts.

On a Sunday in San Francisco’s Chinatown, the fragrance of sandalwood incense along with the measured chants of Buddhist devotees float wistfully down from the Gold Mountain Sagely Monastery. The echoes of both rest ardently on the threshold of the the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu Studio The school, named after the renowned sifu, is as much a fixture of the Chinatown community as the man himself. In many ways, it is hard to separate the two as Grandmaster Wong has invested so much of himself into his art and students that both have a strong reputation in the world of Chinese martial arts.

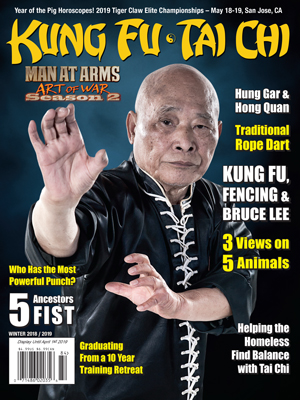

Y.C. Wong is one of the first pioneers to bring Kung Fu to American shores. Adding up his many accomplishments – the multitudes of students he has taught over the last sixty years, his incredible proficiency in the styles of Hung Gar Kuen (洪家拳), Pek Kwar (劈掛拳), Tai Chi (太极), Bagua (八卦掌), and Yi Chuan (意拳), along with countless inspiring performances – one finds that his impact on Kung Fu is greater than the sum of these parts.

Humble Beginnings

Y.C. Wong (Yew Ching Wong 黃耀楨), a native of Hoi Ping (開平) in southern China, began his study of Kung Fu at the age of six. He was born into a family with a tradition of practicing Kung Fu with a high regard for Chinese pugilism. His father and a village uncle who had studied in Hong Kong with the famed Hung Gar Kuen Grandmaster Lam Jo (林祖) made sure he practiced diligently. Wong recalls, “My father would give me a single piece of candy as a reward for doing horse stance for an hour. I was so delighted to do this that I asked him if I did horse stance for two hours, could I have two pieces of candy? He agreed and thus my Kung Fu stance training was firmly established at an early age.”

In 1950 at the age of 18, he and his family left Mainland China and moved to the former Crown colony of Hong Kong. Upon the family’s arrival, both he and his father began studying with Lam Jo. Wong continued his studies as a live-in disciple of the legendary master, becoming Lam Jo’s assistant, practicing Kung Fu alongside him, and assisting both in teaching the younger students as well as performing the practice known as Dit Dar (跌打) in the master’s bone-setting clinic.

In 1960, Wong started his first Kung Fu school in Hong Kong. Later, in 1963, he immigrated with his family to the United States, passing through San Francisco, then settling in Ohio where his sponsoring relatives lived. While residing in the Buckeye State, Wong worked long days throughout the week and had no time to practice Kung Fu. Several years passed and he finally found himself with some time off from work. That evening, he practiced the famous Tiger Crane set of the Hung Gar system. The following morning, he awoke with aches throughout his body and realized that he had been away from Kung Fu practice for far too long. He yearned to have someone to practice Kung Fu with.

This prompted him to move his family to San Francisco where he established friendships with fellow masters. One of the earliest Kung Fu friends he met in the City by the Bay was renowned Hop Gar (俠家拳) Grandmaster David Chin. In 1967, Wong established his first Kung Fu school in the city’s bustling Chinatown.

The beginning of his career as one of Chinatown’s premier Kung Fu instructors was not without its challenges and potential dangers. Grandmaster Wong recounts that navigating the unique landscape of the 1960s Chinatown Kung Fu community was no easy task. However, one of his personal guiding principles was that of mutual respect.

Soon after arriving in San Francisco, he took a morning stroll through Chinatown’s Portsmouth Square and came across the nearby school of the already established Hung Sing Choy Lay Fut (鴻勝蔡李佛) Grandmaster Lau Bun (劉彬). Within the hallowed martial hall of this formidable master was an altar.

You could make a monetary donation known as “Present Flower Oil” (sheung heung yau 上香油) and have your name along with donation amount written on a slip of paper tacked to a board hanging on a nearby wall. Wong recounts that he voluntarily made a $5 donation to the school even though it was just his first time visiting. Little did he know that this kindly gesture would serve to protect him from the hostilities of a very adept Kung Fu practitioner.

Shortly thereafter, a local Chinatown sifu took great offense upon hearing the news of Wong opening a Kung Fu school in the neighborhood. This martial artist was known for having strong fingers and could pry the metal cap off a glass bottle of Coca Cola using only his thumb. In a fit of anger, he prepared to challenge Y.C. Wong to a duel.

Fate however, had different plans. The aforementioned sifu was in fact a student of Lau Bun. The old master himself interceded and stopped the challenge before it was even issued. “Don’t challenge him. Y.C. Wong is respectful and has paid a visit to me and my school. He understands martial etiquette,” said the old master. The student had no choice but to heed the instructions of his teacher and thus began the illustrious martial career of Y.C. Wong in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

The First Large-Scale Demonstration of Kung Fu

In 1968, Kung Fu had yet to become a household name. It was still three years before Bruce Lee would star in the film The Big Boss and four years before David Carradine would appear in the aptly named TV series, Kung Fu. It could therefore be stated that North America’s first real taste of Chinese martial arts came via Grandmaster Wong’s efforts in putting forth the very first large-scale Kung Fu demonstration in North America along with other sifus including Chris Chan, Jack Man Wong, and Brendan Lai.

Organizing the event was no easy task as he faced stalwart opposition from some of Chinatown’s old Kung Fu guard. One such master took a particularly abrasive stance when Y.C. Wong and Chris Chan spoke to him about the event. The old master’s first response was dismal and cutting in its tone. “You will not be successful,” he sneered.

Ever the diplomat, Y.C. Wong replied, “If we are not going to be successful, perhaps your presence can help us. Maybe you could advise us on how to be successful in our venture?”

“I will not come to your event," the old master replied in an admonishing tone. "I will not support you in any fashion and you will fail.”

Despite this setback and other opposition he faced, Wong persisted in his efforts to organize the event. Soon he had galvanized a sizable portion of the local Kung Fu community into sharing their art with a western audience at the San Francisco Civic Auditorium.

The day of the exhibition arrived and the auditorium was brimming with excitement. Wong and his school gave an astounding performance of both the Hung Gar and Pek Kwar systems to the delight of the audience. Other demonstrations showcased the outstanding skills of Kung Fu luminaries such as Chris Chan’s explosive, rapid-fire Wing Chun (詠春) system and Kenneth Wong’s lightning-fast Hung Sing Choy Lay Fut style. However, it was Wong’s performance of the esoteric weapon known as the Plum Flower Double Chain Whip which held the audience in a state of rapture.

Tendrils of silver lashed out from both his hands, flying forth with a blinding burst of speed. Some in the audience questioned what they were witnessing, never having seen such ferocity and savage grace in a weapon performance. All they saw was twin bolts of silver dancing through the air, whipping about like wild mares galloping across some distant continent. As his performance reached its crescendo, the two steel whips flew backwards. The metal links retracted, folding neatly at the command of wooden handles grasped by corresponding hands. It was then that the audience saw the weapons for what they were: links of inanimate chain which he had brought to life by sheer force of will.

The large audience was enthralled by all that they witnessed, and the event was a resounding success, with coverage in several prominent periodicals. This unprecedented demonstration would be the flashpoint leading into the Kung Fu craze of the seventies, with Wong himself the one who ignited the flame within the hearts and minds of those present that fateful day.

Teaching Chinese and Non-Chinese Alike

In the lore of the American Kung Fu experience there are many xenophobic tales. Stories abound of Chinese masters who are reluctant or outright opposed to teaching non-Chinese students. While popular opinion may state that this was once the norm, it was never the case in regards to Grandmaster Wong, who has always been willing to share his art with people of all races and backgrounds.

As one of the first instructors to teach Kung Fu openly in the United States, Wong was one of the first to teach the art to Non-Chinese students on American soil. While this was progressive in its own right, few knew that he was already teaching westerners the art of Hung Gar as early as 1960 in Hong Kong. One of his first students in this regard was a white Mormon missionary. “We would meet early in the morning before breakfast, and I would teach him," notes Wong. "Upon finishing, he would leave to do his work preaching for the day.”

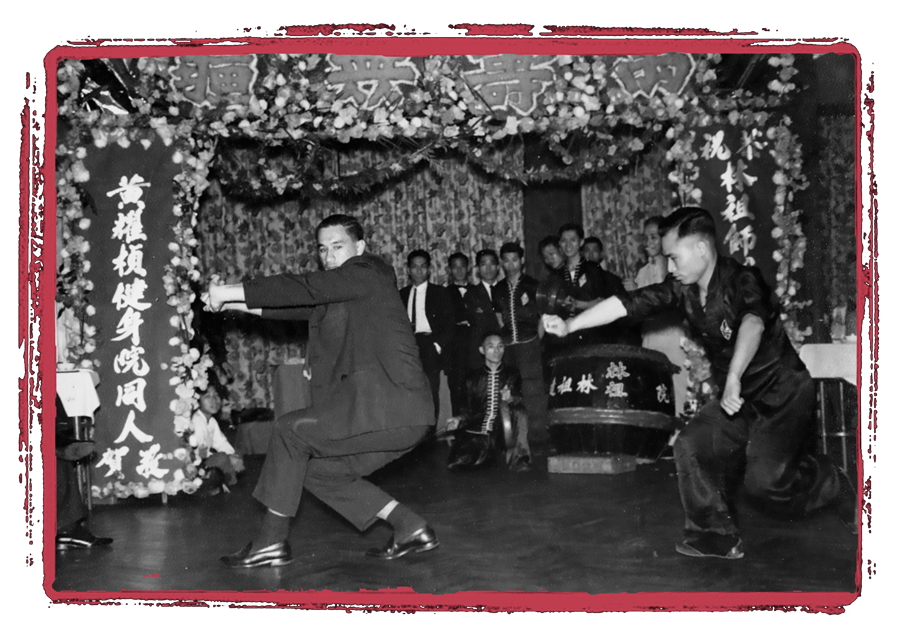

This was not a clandestine exchange of knowledge. In 1961, during a birthday celebration for Wong’s teacher Lam Jo, Wong proudly presented this same Caucasian student, who performed Kung Fu alongside him much to the delight of the local Hong Kong martial arts community in attendance.

This type of progressive view and inclusivity was not something that he arrived at via any particular revelation. Rather, it was, and still is, part of the fabric of his mindset to share his knowledge with people of all backgrounds and ethnicities. While the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu Studio is deeply rooted in Chinatown, it has always been comprised of students representing the full spectrum of the American experience.

Throughout the decades, Wong has taught not only at his school in Chinatown but also at locations in Sacramento, Stockton, and Oakland. This, along with his dedication, has resulted in him producing many students who have become masters in their own right. His son, Ray Wong, is a prime example of this. Ray contributes heavily to his father’s school and shares his razor-sharp skill along with boundless passion for the art.

In addition to his son, one group of students are amongst the most notable of his lineage. Collectively known as “The Wong Family” (Lester, Leland, Aaron, Craig, Anthony, Darryl, Kyle, Megan, and Jason), the group consists of a single family and spans two generations of students who have been with Y.C. Wong since his early days in San Francisco. While they share the same surname as their sifu, they are not related to him by blood. However, and most importantly, they exemplify the high quality of Kung Fu which Wong instills in his students and continue to pass on his art as instructors themselves. Other notable instructors of the Y.C. Wong lineage in the United States include Frank Marez of Sacramento, Peter Pena of Arizona, Jacob Brinnand of Palm Desert, and Kurtis Fujita of Los Angeles. Wong’s students in Europe include Ursula Brueckner in Germany, Fabien Latouille in France, and Marco Luglio in Italy.

Year of the Grateful Dead

Shadowy silhouettes swayed back and forth in rhythmic euphoria, infected by the musical intonations of figures basked by auburn moonlight on a raised dais. The Grateful Dead was the Band, the venue was the Oakland Civic Auditorium, and the year was that of the Water Dog, 1982.

The haunting timbre of Jerry Garcia’s voice cascaded across the audience the way night falls upon dusk. Suddenly, the spotlight focused on percussionist Mickey Hart who began a familiar Grateful Dead drum solo which in turn, transformed into a staccato beat not normally heard at any rock concert.

Hours earlier, Wong and his son Ray came to rehearse with the seminal band’s percussionist. Through an introduction by a mutual acquaintance, Mickey Hart had invited several Kung Fu schools including the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu Studio to demonstrate Martial Arts and Lion Dance during a special Chinese New Year Concert. Wong himself went over the iconic drum beat of the Chinese Lion Dance with the talented Hart, who easily picked it up in astonishing fashion.

It was this same beat that now echoed through the concert hall. The sound of Mickey Hart’s drum then began to diminish, only to give way and be renewed by that of a classic Chinese Lion Dance drum played by Y.C. Wong Kung Fu’s very own Aaron Wong.

Nearby, a towering man with a burly build raised a sturdy mallet and struck a large gong. The thunderclap resonated across the crowd.

The same spotlight which illuminated the musicians then darted sideways and upwards past the stage like a shooting star returning skyward, to stop on a small platform suspended in the air nearly twenty feet higher than where the band played. Perched on this precarious landing was Grand Master Wong, brandishing a spear directly across from his pupil Anthony Wong, who wielded dual butterfly swords whose blades glinted at the audience like a far-away constellation.

They clashed in epic fashion while performing one of Hung Gar’s most celebrated and dynamic weapon sparring sets. The stage was so small that the two had to engage the skirmish diagonally across from each other so as to not fall off the elevated platform. The routine ended climatically with Y.C. Wong losing his spear, yet defeating his opponent’s blades while empty handed.

The audience roared with applause at the dexterous skill of both master and protege. Yet again, Y.C. Wong had transfixed an audience beyond their wildest expectations with his utter mastery. It was evident that all in attendance were Grateful.

The Czech Connection

During the late nineties, Grandmaster Y.C. Wong would further establish his prominence as one of Kung Fu’s modern pioneers, albeit in a different country: the Czech Republic. Despite this being prior to the internet age, word of the famous Hung Gar Sifu had already spread to the distant land via various magazine articles and martial arts publications.

Several dedicated young men who wished to learn the art directly from him journeyed from the city of Prague to San Francisco. They arrived unannounced, with no prior contact to the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu Studio. Both Grandmaster Wong and his son Ray welcomed them with open arms and began instructing them in the art of Hung Kuen. The Czechs worked tirelessly, absorbing the knowledge at an impressive pace and soon returned to their homeland with their new art in tow.

A strong bond formed between both master and students. Soon Y.C. Wong and Ray began making trips to Prague to further the martial knowledge of their Czech students. This group of students would grow to what is now known as the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu Czech Association. The group is led by Sifus Ales Kocian, Marek Bravnik, Martin Lana, Vaclav Lajcak, Martin Sedlacek, Lukas Radostny, and Tomas Petrus. It has amassed a sizable following and has grown from the single Prague studio to multiple locations across the country in the cities of Havirov, Decin, Kynsperk nad Ohri, and Praha. The tradition of the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu lineage now flourishes in the community of this Central European Country.

Speak Softly, Carry a Big Stick

“If one is to wield a pen with skill, one must wield weapons with skill because weapons provide support for the pen.” –Lam Sai Wing (林世榮)

Such is the introduction to the famed book on the Hung Gar form, Gung Ji Fook Fu Kuen (Taming the Tiger Form 工字伏虎拳) by Great Grand Master Lam Sai Wing. This ideology describes much of Y.C. Wong’s ability to handle adversity with grace and dignity, yet with the strength to back up these words with action. During his career in martial arts, there have been times when the open hand of diplomacy required assistance from the strength of the closed fist. Wong himself has always found the proper balance between these two ideologies and in one instance represented the dichotomy of both masterfully.

One evening, a very aggressive heckler called the Y.C. Wong Kung Fu Studio. Wong himself answered the phone. The caller insulted him, insulted his Kung Fu, and then proceeded to threaten him. Despite being yelled at in such a hostile manner, he did not lose his temper. However, his response was calm and measured, yet very firm in its delivery.

He replied, “I am sorry you feel that way and I have no bone to pick with you. But we will be open an extra hour tonight just for you. So please, do come down.”

Suffice to say, the caller promptly hung up and did not take him up on his offer despite the extended hours at the studio that evening. Once again, Y.C. Wong exhibited the ideal characteristics of a true martial arts master: The ability to make peace yet the resolve to handle conflict in the most resolute manner.

A Masterful Legacy

The heritage of Y.C. Wong is one of excellence, steeped in progressive tradition. A lifetime of teaching Kung Fu has made him a pioneer while living the martial way has made him a legend. At various martial art events it is plain to see he is held in high regard by his peers as well as the generations of masters and students who follow the trail which he blazed so many decades ago. At an advanced age of 86, he remains quick to share his knowledge with those who are still astounded by the speed, power, and grace of his masterful movements. The school he established over 50 years ago still sits firmly, embedded in the heart of San Francisco’s Chinatown. The reputation and adoration he established so long ago still sits firmly in the hearts and minds of his colleagues and students who call him by the well-earned title: Sifu.

| Discuss this article online | |

| Kung Fu Tai Chi magazine winter 2019 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2019 .

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

About

Kurtis Fujita :

Sifu Kurtis Fujita is a student of Grand Master Y.C. Wong and Grand Master Raymond K. Wong. He is the Founder and Head Instructor of Tiger Crane Kung Fu in Simi Valley, California. Sifu Fujita serves as the Los Angeles Chairman of the United States Traditional Kung Fu Wushu Federation and is the Hung Gar Advisor to the International Traditional Kung Fu Association. He can be contacted at: email: instructor@tigercrane.net; online: TigerCrane.net; Facebook: facebook.com/tigercranekungfu; Youtube and Instagram: tigercrane805

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article