By Gene Ching and Gigi Oh

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

Modern Wushu has been a struggling sport from the start. A child of the Cultural Revolution, it was dismissed by many traditional Chinese martial arts exponents as propagandist and ineffective. But it’s the best shot that the Chinese martial arts has for getting an Olympic event. Last June, Wushu was teased with making the semifinal list of eight new contenders for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. But by September, the IOC announced that Wushu failed to make the next cut, rejected alongside bowling and squash. Baseball/Softball, Karate, Skateboarding, Sport Climbing and Surfing moved on to the next round, and the ultimate winner will be decided this summer at Rio De Janiero. Just like at the Beijing 2008 games, Wushu’s Olympic pipe dream was crushed. The International Wushu Federation responded tepidly, saying that they “were disappointed although not completely surprised” and that they were optimistic about trying again in 2024. But with such a lukewarm attitude, does Wushu really have what it takes to be Olympic anymore?

Modern Wushu has been a struggling sport from the start. A child of the Cultural Revolution, it was dismissed by many traditional Chinese martial arts exponents as propagandist and ineffective. But it’s the best shot that the Chinese martial arts has for getting an Olympic event. Last June, Wushu was teased with making the semifinal list of eight new contenders for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. But by September, the IOC announced that Wushu failed to make the next cut, rejected alongside bowling and squash. Baseball/Softball, Karate, Skateboarding, Sport Climbing and Surfing moved on to the next round, and the ultimate winner will be decided this summer at Rio De Janiero. Just like at the Beijing 2008 games, Wushu’s Olympic pipe dream was crushed. The International Wushu Federation responded tepidly, saying that they “were disappointed although not completely surprised” and that they were optimistic about trying again in 2024. But with such a lukewarm attitude, does Wushu really have what it takes to be Olympic anymore?

Although the Olympics have long been the ultimate goal of Modern Wushu, the measure of Wushu should not be judged by this alone. Today, Wushu is included in many other major sports events. In Asia, it is included in the Asian Games, East Asian Games, South Asian Games and the Southeast Asian Games. Internationally Wushu is an event at the World Games, the Mediterranean Games and, of course, the World Combat Games. And in 2017, it is likely to be included at the XXIX Universiade (a.k.a. World University Games), which will be held in Taipei, Taiwan. And Wushu’s own internal events are still going strong. From November 11 to 18, the 13th World Wushu Championship was held in Jakarta, Indonesia, with special guest, Wushu’s golden star, Jet Li.

As a developing sport, Wushu is constantly changing its rules. Most of these changes are part of an attempt to make the sport more inclusive. Chinese martial arts encompass the most diverse traditions of any nation. It is impossible to compress all of those into a few divisions. Last year in Jakarta, four new divisions were added there. These were divided by sex: for men, Xingyiquan (形意拳) and Guandao (關刀); for women, Baguazhang (八卦掌) and Twin jian (雙劍).

The Guandao is a long halberd and the Twin jian are double straight swords; both weapons can be converted to Wushu easily. Wushu has standardized its arsenal of weapons to be lighter, flashier and noisier in an attempt to garner more audience appeal, so much so that they can hardly be called weapons anymore. Emasculated of any lethality, they are closer to the props used in the Olympic sport of rhythmic gymnastics.

Xingyi and Bagua are traditional internal martial arts akin to Tai Chi. Tai Chi, or Taijiquan (太極拳) as it is formally spelled for Modern Wushu, is really the only style that has retained some of its uniqueness on the competition carpet. Beyond the Taijiquan division, the sport of Wushu is divided into northern and southern fist, or changquan (long fist 長拳) and nanquan (southern fist 南拳), for empty hand routines. The weapons are all nondenominational in that they are not attached to a specific style, with the exception of the southern sword (nandao 南刀) and Taiji sword (taijijian 太極劍). Xingyi and Bagua are very specific. Like Taiji, they encompass several different lineages which vary dramatically. The architects of Modern Wushu are attempting to preserve these two traditions more genuinely than what was done with Taiji. The Modern Wushu version of Taiji mashed the dominant styles of Taiji together into a competition form and added extreme flying kicks, some of the most difficult moves in the entire sport, much to the chagrin of traditional Taiji players.

Master Jia Shusen (贾树森) is one of the leading Baguazhang masters in the United States. He is a staunch traditionalist with an impeccable Baguazhang pedigree. A highly decorated champion and the author of the book, Getting Started in Bagua (Baguazhang Rumen 八卦掌入门), Jia was featured on numerous programs, magazine articles, instructional posters in China before immigrating the United States in 2008. Jia is enthusiastic about the promise of Modern Wushu Baguazhang. “I agree with the new competition,” says Jia in Mandarin. “It’s easier to promote. But they cannot deviate from their basics. Each system has its own characteristics.”

Bagua in Beijing

Born in Beijing in 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was founded, Master Jia began his study of Baguazhang under Master Li Wenzhang (李文章) late in life, when he was thirty. However, prior to Bagua, Jia practiced several other styles of Kung Fu, beginning with Shaolin at age eight, so he was already skilled in the martial arts. In 1993, at the behest of Master Li, Master Jia became a disciple of Grandmaster Sun Zhijun (孙志君; born 1993). Grandmaster Sun is the National Intangible Cultural Heritage Inheritor representing Baguazhang. Sun’s lineage is Cheng family Baguazhang, in direct line with Dong Haichuan’s (董海川; 1797 or 1813–1882) disciple, Cheng Tinghua (程廷華; 1948–1900). Grandmaster Dong founded the style, after which his disciples created variations on it. The other major lineage is Yin, named for Grandmaster Dong’s other disciple, Yin Fu (尹福; 1814–1909). Master Jia studied both Cheng and Yin from his first Bagua master, Master Li. As Master Jia explains, “Cheng and Yin family, Liang (梁), Fan (范), there are more. Yin is more like changquan. It has movements that are very fast and crisp. Cheng Tinghua was originally trained in Shuaijiao (a throwing and grappling system 摔跤) and Xingyi. It’s more like a swimming dragon. I started with Yin and then switched to Cheng. I just like Cheng better.”

Wikipedia lists over fifteen different styles of Baguazhang, but the four Master Jia named – plus Shi (史) family Bagua – are considered the major five. Chinese love the number five. Yin style is described with five qualities: cold, springy, hard, crisp and fast. It is also called the “hard palm method (gang zhang fa 刚掌法).” Although Master Jia holds Yin style in great regard, his personal preference is Cheng style. This stems partly from his passion for another practice of his, Chen family Taiji (陳家太極). Jia is also a disciple of Grandmaster Feng Zhijiang (冯志强; 1928–2012), the founder of Hunyuan Taiji (混元太极), who was himself a pupil of the prominent exponent of the style, Chen Fake (Note: Fake is pronounced “fah-keh” 陳發科; 1887–1957).

“There is a lot of similarity between Chen and Bagua. Chen Fake style – Chen Fake went to Beijing so his Chen is a little different. Beijingers call it ‘Chen Fake Taiji.’ Chen brought the 1st and 2nd routines from Chen Village and modified them. The signature moves are all the same but the transitions are different. The power of this Chen style is very similar to Bagua. You must open your joints and extend your tendons. You need to be more flexible. The original principle behind the fajing (emitting power 發勁) was similar. Both are good for combat and longevity. Feng Zhijiang created Hunyuan Taiji, which is mostly for health and longevity.

“Not all fajing is explosive. A lot of people use a lot of muscle for fajing with Chen style. After training Bagua, the muscles are not square, but long and soft. You need muscle for fajing, but the difference is whether you get your primary energy from your dantien (energy center 丹田) and secondary energy from your muscles, or the other way around. The traditional Chen routine paoquan (cannon fist 炮拳) uses more muscle. Doing changquan is like a stick – it’s straight. Bagua is more spiral, like a twisting rope. Chen Taiji spirals too.”

Mixing Martial Arts

Despite drawing these parallels, Master Jia firmly believes in discriminating between different styles of Chinese martial arts. Jia feels it is of the utmost importance to stay true to the tradition. “Lately you hear of Xingyi Bagua, Shaolin Bagua, Taiji Bagua – why create new styles? Bagua is Bagua. Chinese martial arts are like Chinese banquets. Each dish has a different flavor. Mix it all up makes everything bland. Most Xingyi Bagua, Taiji Bagua and so on began because they see the benefit of Bagua. They just add it into their systems to make it look like they have more. Some just do a few moves of Xingyi, then a few of Bagua. I don’t agree with mixing. Stay within your system.”

However, staying consistent within your system doesn’t mean to be constricted within it. You can study as many systems as you can remember as long as you don’t mix them up indiscriminatingly. Jia studied all three of the major internal styles of Chinese martial arts: Baguazhang, Taijiquan, and Xingyiquan. At the same time he was studying Bagua with Master Li, he was also studying Wu style Taiji (武氏太極) and Xingyiquan with Master Wang Rongtang (王荣堂; 1913–1996). Bagua and Xingyi are often paired, as Bagua is basically circular and Xingyi is fundamentally linear. They are the other two dominant internal styles of Kung Fu beyond Tai Chi. Jet Li’s The One (2001) dramatized this Xingyi and Bagua relationship in a unique science-fiction film. It was an exceptional portrayal for Hollywood, but only Kung Fu practitioners understood the underlying martial-philosophic allegory. (Jet discussed this with Kung Fu Tai Chi in our November+December 2001 cover story). Master Jia views the relationship between the two styles far more simply.

“In Xingyi, only piquan (chopping fist 劈拳) is a palm. Bagua has only one fist – a back fist – in fanbeiquan (反背拳). The simple difference is this. Historically, Dong Haichun learned many styles. His most famous students were all famous in Xingyi first. Many say Xingyi and Bagua are one same family. Xingyi starts harder, but when you learn Chinese martial arts, you must have gang (hard 剛) before rou (soft 柔). If you just try to learn soft, you cannot achieve anything. We say, ‘Under Heaven, martial arts are one family (tian xia wushu yi jia 天下武術一家).’ You can learn all these different movements with one breath.”

The Circles of Cheng Baguazhang

Baguazhang literally means “eight diagram palm,” although diagram is a concessive translation. Gua refers to a very specific type of Daoist diagram, often referred to as a trigram. Gua is composed of solid and broken lines in three-line stacks that represent the dualistic principles of yin and yang. When the all solid, all broken and all the possible combinations of solid and broken lines are assembled, their sum comes out to eight. Each of these eight trigrams is associated with different cosmological meanings like elements, cardinal directions, emotions, parts of the human body, animals and so forth. When two trigrams are combined, the resulting sixty-four hexagrams are used as a mystic forecasting tool akin to fortunetelling Tarot cards. This system of divination is known as I Ching (易經) or, as conventionally translated, the Book of Changes. The I Ching can be traced back to China’s Western Zhou period (1000–750 BCE).

The martial art of Baguazhang maps onto this Daoist classic with a foundation of eight techniques – or eight palms – that are the building blocks of the system. According to Master Jia, in Cheng Bagua, this begins with a stationary practice of Bagua that just focuses on the palm techniques called Dingshi Bagua (Dingshi means “fix style” 定式八卦掌). The next level is the eight palms, each of which is combined with footwork. Then comes the Changing Palm (Bagua Zhuan Zhang 八卦转掌) where the eight palms are combined in 16 turning techniques. After that, there are three more: Bagua Mother Palm (Bagua Mu Zhang 八卦母掌), Bagua Linking Palm (Bagua Lianhuan Zhang 八卦连环掌) and Swimming Body Palm (Youshen Zhang 游身掌).

Bagua has one of the most unique arsenals of any Chinese martial art. In addition to some of the Kung Fu core weapons like staff (gun 棍), straight sword (jian 剑) and spear (qiang 抢), it has a unique single-edged sword, the Bagua dao (八卦刀). “Bagua doesn’t have a regular dao, only the Bagua dao. It’s big, over four feet long, and weighs over three pounds.” On top of that, Bagua has the distinctive Deer Horn Knives (lujiao dao 鹿角刀) solely practiced by this style. Deer Horn Knives are a pair of handheld weapons constructed from intersecting crescent blades with a handle. Bagua practitioners also still use very ancient pole arms, the double snakehead spears (shuang tou she 双头蛇) and the yue (鉞), a broad axe-head mounted atop a pole that was prevalent during China’s bronze age (roughly 2000–700 BCE). Bagua also has an unusual selection of short weapons like the Emei piercers (Emei ci 峨嵋刺), which are long thin double-pointed spikes held in both hands with a swivel ring and named for Emei mountain in Sichuan Province, and the Judge’s Pen (panguan bi 判官笔), which is a small thick rod slightly wider than the fist with points on either end. Specific to Yin family Bagua is the Yin shi ganbang chui (尹氏乾棒槌), a unique rod and hammer like weapon. And there’s one of Master Jia’s personal specialties, the Fly Whisk (fuchen 拂尘). Various Bagua lineages have even rarer unique weapons; this is only an overview from Master Jia’s experience.

Even overlooking the weapons, how can Modern Wushu resolve the variations in Baguazhang in a way that provides a fair playing field for competitors? Master Jia is fully aware of the challenges facing Modern Wushu Baguazhang and believes there is great potential. Although he was not involved in the development of Baguazhang into a Wushu sport, he was instrumental with another aspect of Wushu, the combative full-contact sport of Sanda. From the early ‘80s through to the ‘90s, Master Jia worked together with Professor Mei Huizhi (梅惠志) on the development of Sanda. Jia served as Deputy Secretary General, overseeing the organization of teaching methods and competitions for Sanda.

Nowadays, with the emphasis on health, the internal styles of Bagua, Xingyi and Taiji are often disregarded as practical combat methods, especially in sport fighting. However, Master Jia has participated in projects that were very combat-focused outside of the Sanda ring too. In 1998, Jia joined forces with Master Han Jianzhong (韩建忠) and others to found the Beijing Badaling Great Wall Military Academy (北京八达岭长城武校) in Yanqing County, Beijing. Jia was the first president of that Academy. His involvement in Sanda earned him recognition as one of the Top 100 Boxing Fighters (搏击百杰) by the Martial Research Association in 2007. “The founder of each Chinese martial arts system already passed the test of combat. These styles are not created from nothing. That’s the essence of each style. That should not change.”

From Harming to Healing

Today, Master Jia is as focused on healing as he is on martial arts. Traditionally, many Kung Fu masters were also Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) doctors. He began studying TCM in 1971 under Ma Zitong (马子彤) and earned his degree in TCM. In 2000, he became a disciple of one of the most renowned TCM exponents, Professor He Puren (贺普仁), who was known as the Acupuncture Dean (zhenjiu taidou 针灸泰斗). When local people in the martial arts community get injured or ill, they seek Master Jia. “There are four principles that govern Wushu. First, it must have a combat origin. Second, it must cultivate health. Third, it must cultivate the mind. It must increase peacefulness and spirituality. And fourth, it must promote wude (martial morality 武德). The Chinese martial arts propound Confucian ideals. I would add two more principles for today. Fifth, Wushu can be for performance. And sixth, it should be something that can be promoted to the general public. These last two are modern purposes.”

As the Chinese martial arts continue to spread around the globe, it must change and grow. The sport of Modern Wushu has been one of the earlier attempts of China to meet the expectations of today’s competitive world. The evolution of Taiji into a health-promoting exercise has made it into one of China’s greatest exports. However, as the Taiji diaspora has expanded, the art has changed radically, so much so that most of the general public has no idea that it is a martial art. Baguazhang has the potential to ride Taiji’s popularity coattails particularly now with Wushu. However, knowing how Wushu changed Taiji for competition, Bagua hopes to proceed more cautiously to protect its integrity. As Master Jia sees it, “A national governing body to regulate Bagua is a good idea.”

| Discuss this article online | |

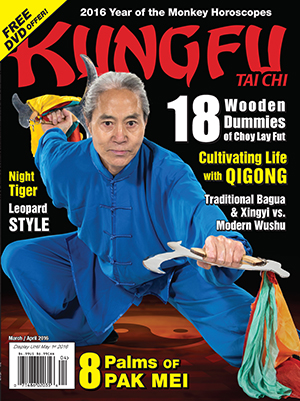

| Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine March + April 2016 |

Click here for Feature Articles from this issue and others published in

2016 .

Buy this issue now , or download it from Zinio

About

Gene Ching and Gigi Oh :

For video of Master Jia Shusen’s Baguazhang, visit the KungFuMagazine.com YouTube channel.

![]() Print Friendly Version of This Article

Print Friendly Version of This Article